Social and economic inequities play a critical role in understanding why numerous diseases disproportionately burden certain communities in Canada and around the world. COVID-19 has not been an exception. Some people are more likely to get infected by COVID-19 and/or suffer severe outcomes such as hospitalization and death. This higher risk is often linked to social determinants of health, which include income or material deprivation, employment, education, and racialization, among others. Social determinants have also had a measurable effect on access to vaccines and vaccine uptake in Canada.

Several CITF-funded studies have focused on specific populations that have been found to be at higher risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 and/or who have suffered more severe outcomes due to the intersection of health and social factors. They have also looked at vaccine access and uptake, as well as barriers to vaccination. Casting light on these issues can guide policies and practices which can contribute to overcoming these challenges.

In this month’s research synthesis, we surveyed CITF-funded research, complementing it with other findings, to respond to the following questions:

- How have social determinants of health (income, occupation, culture, bedroom density, and language) impacted SARS-CoV-2 infection rates, severe COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in Canada?

- How have the social determinants of health impacted access to vaccines and vaccine uptake in Canada?

- What measures are being recommended to better reach priority populations most at-risk of COVID-19?

PART 1

The impacts of social determinants of health on infection, hospitalization, and death rates due to COVID-19

Here, we have looked at how some social determinants of health – e.g. income or material deprivation, employment, household and bedroom density, education, and culture/ethnicity – have played a role in COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death rates of people in Canada.

Income or material deprivation

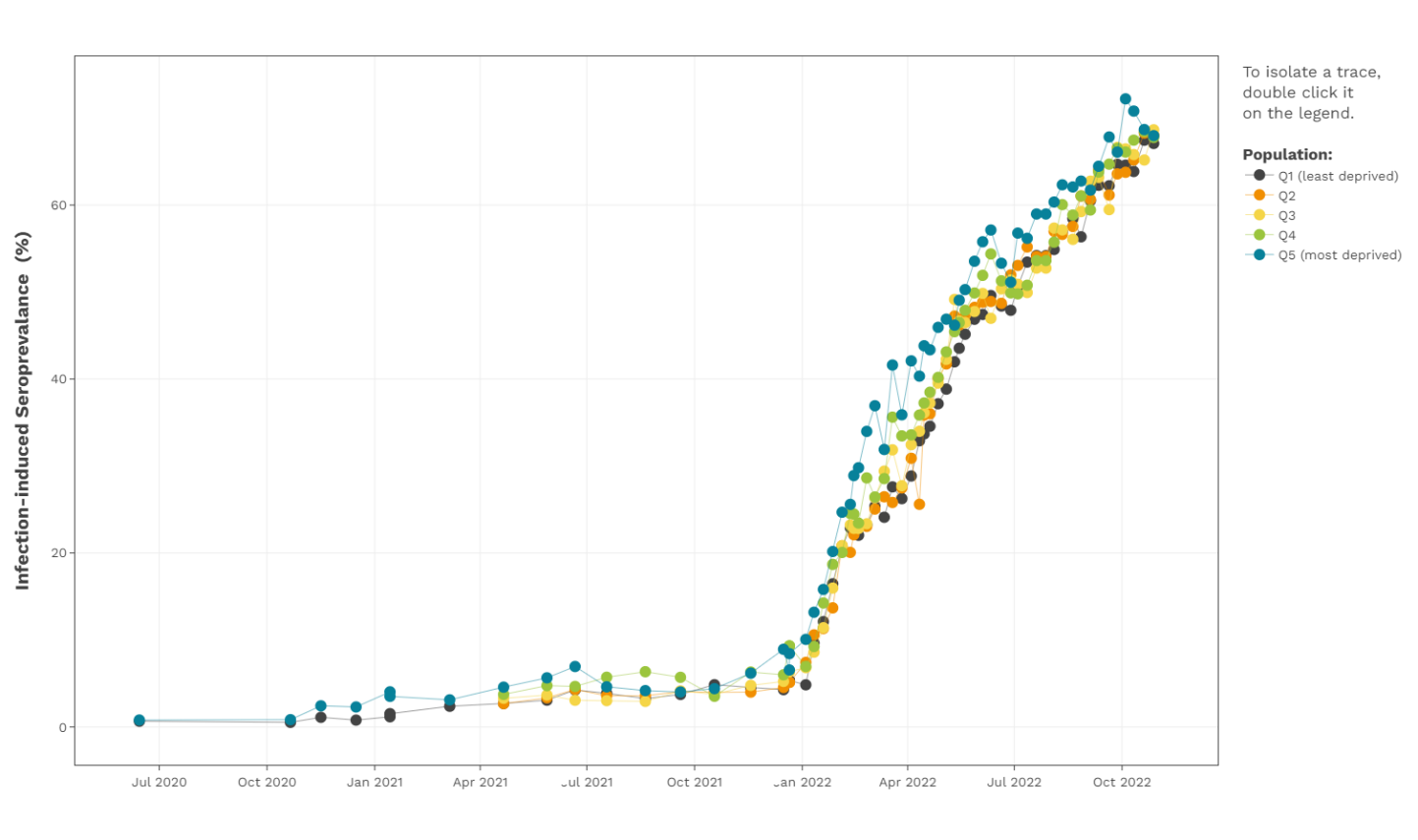

Economically marginalized communities faced disproportionately higher risks of infection and death from COVID-19 across Canada, particularly during the first few waves of the pandemic. These disparities were expected to dissipate in subsequent waves, given the efforts undertaken to ensure equitable protection and access to vaccination, but that did not prove to be the case.

CITF-funded data from Canadian Blood Services, encompassing all of Canada (except Quebec and the territories), has highlighted how the gap in infection-acquired seroprevalence between the most and least materially deprived has persisted throughout the pandemic. This gap seemed to close slightly in more recent months, since the emergence of Omicron and its sub-variants (BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, and BA.5). The most materially deprived communities (Q4 and Q5)The Material Deprivation index is an indicator for the lack of goods and services (deprivation) in a participant’s neighbourhood, based on the first three digits of their postal code (FSA). The index was developed was Statistics Canada using data from the 2016 Canadian Census on household income, unemployment rate, and high school education rate. Whereas Q5 represents the most deprived, Q1 represents the least deprived. have been hit the hardest during all seven COVID-19 waves to date (see the figure below).

Several other CITF-funded studies have also identified higher seroprevalence in households with lower income (1, 2). Data from Ontario and Quebec illustrate some striking findings.

Ontario

- Between February 2020 and December 2021, people living in neighborhoods experiencing the highest level of material deprivation were 2.7 times more likely to be hospitalized and sent to the intensive care unit (ICU) and 2.9 times more likely to die from COVID-19 compared to people living in higher income neighborhoods (3).

- A CITF-funded study led by Drs. Sharmistha Mishra and Sharon Straus (University of Toronto) found that, since the beginning of the pandemic in Ontario, hospitalizations and deaths have remained concentrated among the 20% of the population living in the lowest-income neighborhoods (4).

- Mishra and Straus’ estimates also revealed that while vaccine uptake and SARS-CoV-2 infection rates were about the same between low- and higher-income groups, lower income groups were 10 times more likely to be hospitalized or die due to COVID-19.

- Another CITF-funded study, led by Drs. Mishra and Jeffrey Kwong (University of Toronto), identified an increased risk of COVID-19-related deaths in people with lower income (5).

Quebec

- Quebecers living in very disadvantaged neighborhoods were 2.75 times more likely to get COVID-19 than persons living in high-income areas during the first wave; 2.24 times more likely in the second wave; and 2.07 times more in the third wave (6).

- The mortality rate due to COVID-19, as of July 17, 2021, was 33 per 100,000 inhabitants in high-income areas, whereas in very disadvantaged neighborhoods, there were 77 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants (6).

- During the first part of the Omicron wave (from January until March 2022), CITF-funded data from Héma-Québec reported that the most materially deprived neighborhoods (Q4 and Q5) had 1.2-1.8 times more SARS-CoV-2 infections than the least materially deprived neighborhoods.

Employment

Evidence suggests that those workers who were deemed essential, and who continued to serve the needs of society throughout the pandemic, experienced a disproportionate burden of infection, transmission, and death. Although some essential workers, such as nurses, doctors, teachers, police officers, and firemen, have stable, higher paying jobs, many other essential worker positions are precarious, contractual, and part-time, often not offering any benefits and, thus, families relying on such employment end up living in low-income communities (7).

- CITF-funded researcher Dr. Upton Allen (University of Toronto) found that frontline workers were more than three times as likely to be seropositive compared with non-frontline workers (unpublished results).

- A CITF-funded study focused on Montreal North led by Dr. Jack Jedwab (Association for Canadian Studies) and Dr. Simona Bignami (University of Montreal) highlighted that healthcare workers had the highest seroprevalence among 18- to 54-year-olds approximately 30%, in August – December 2021) in the borough (unpublished data).

- The same study also mentioned that preschool, primary or secondary teachers had the second highest seroprevalence rate at 23% (unpublished data).

- A CITF-funded study led by Drs. Mishra and Mathieu Maheu-Giroux (McGill University) identified that higher rates of infection were often correlated with being an essential worker (2) as defined by the National Occupational Classification (those not able to work remotely) (2).

- As of January 2022, there were over 150,000 recorded cases of COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Canada. Of those, at least 46 died from COVID-19 (8).

- Another study from Drs. Mishra and Kwong identified an increased risk of COVID-19-related mortality among those living in neighbourhoods with a higher proportion of essential workers (Hazard RatioA hazard ratio is the ratio of the risk of an outcome in one group relative to the same risk in the control group over a unit of time. (HR)- 1.28) (5).

- A study published in the Annals of Epidemiology by researchers from the University of Toronto mentioned that cumulative per-capita rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths from January 2020 to January 2021 were 3.3-fold and 2.5-fold higher, respectively, in neighborhoods with the highest concentration of essential workers when compared to neighborhoods with the lowest concentration of essential workers (9).

Household and bedroom densityBedroom density refers to how many people occupy each bedroom in a home and is intended as a more accurate measure of household density.

The amount of living area available to a person has impacted opportunities to isolate and distance from others within the home thereby affecting the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. In addition, those living in apartments and transiting through common spaces also have been found to have had higher rates of infection.

- Several CITF-funded studies have identified higher bedroom density (>2 persons per bedroom), alongside race/ethnic minorities and lower household income as factors associated with higher seroprevalence (1, 2, 10).

- A CITF-funded study led by Drs. Roger Zemek and Marc-André Langlois (University of Ottawa) also identified, as predictors of household transmission, household density (number of people per bedroom), the relationship between individuals, and the number of cases in the household (10).

Modelling analysis from Statistics Canada showed that the likelihood of dying from COVID-19 was significantly higher for (11):

- Those inhabiting dwellings with higher bedroom density ,

- Those living in an apartment, and

- Those living in households with low income.

- A CITF-funded study from Drs. Mishra and Kwong identified an increased risk of COVID-19-related deaths among people living in apartment buildings (HR- 1.25) and large households (>3-6 people/dwelling) (HR – 1.30) compared to people living in a medium sized household (2-3 people) (5).

- COVID-19 mortality rates have been found to be 2.5 times higher among those living in high-rise apartments than among those living in single detached houses in Quebec, and 2 times higher in Ontario (12). Living in multi-residence buildings, like apartments, necessitates more frequent close contact between people and touching surfaces in high-traffic, shared areas like lobbies and elevators (12).

Race/Ethnicity

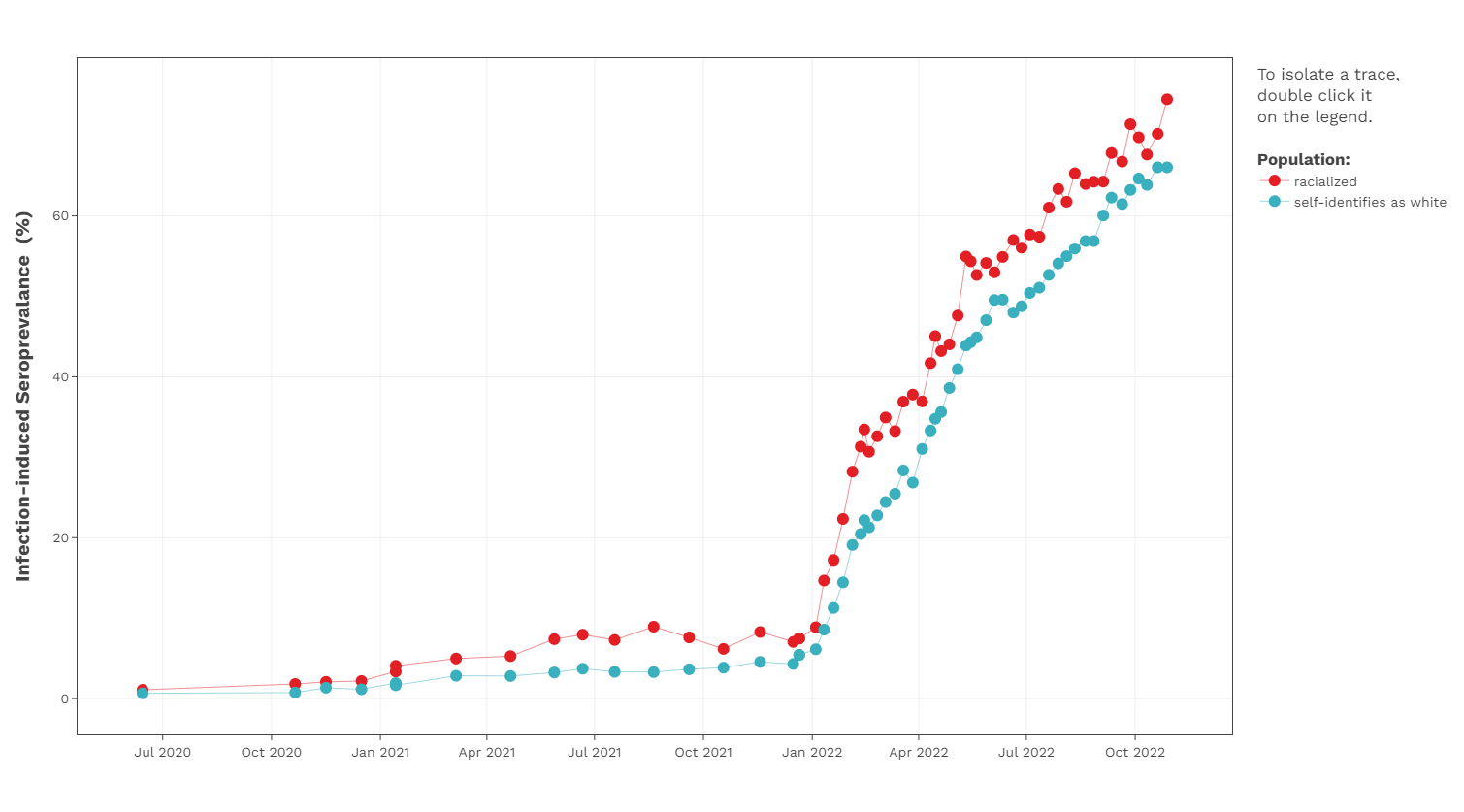

Racialized communities have been harder hit by the pandemic than white communities. This higher risk in racialized communities reflects the intersection of factors that at times includes an over-representation of essential workers, lower household incomes, and long-standing structural impediments to accessing healthcare.

- CITF-funded Canadian Blood Services data have highlighted that self-declared racialized donors have had higher infection-acquired seroprevalence than self-declared white donors since the start of the pandemic (see the figure below).

- Allen’s study has found that race and place of residence intersect and influence the risk of seropositivity. Specifically, racialized individuals – and Black people in particular – living in low-income communities are at greater risk of Infection (unpublished results).

- A CITF-funded study from Ontario led by Drs. Mishra and Kwong further highlighted an increased risk of COVID-19-related deaths in areas with a higher proportion of racial minority groups (38.7% vs 27.3%) and recent immigrants (37.7% vs 27.4%) (5).

- People of South Asian descent, the largest non-white ethnic group in Canada (2.6 million people, or 7.1% of the population) (13) have been disproportionally affected by the pandemic (14).

- According to baseline surveys conducted among South Asians in April-June 2021 (15) by the COVID CommUNITY study, led by Dr. Sonia Anand (McMaster University), 33% identified as essential workers (e.g., food processing, manufacturing, transportation, healthcare, education) and 19% reported living in multi-generational family homes.

- Anand also found that, by the third wave of the pandemic (April 14 to July 28, 2021) , about one-quarter of a sample of South Asians in Ontario had serologic evidence of a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- Additionally, the study looked at data from Public Health Ontario, which showed a higher burden of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Peel Region compared to the rest of Ontario between April and July 2021 (over half of residents in the Peel Region of the Greater Toronto Area identify as South Asian Canadians).

- The borough of Montreal North is one of the most densely populated, racially diverse and lowest-income boroughs on the island of Montreal (16). Unpublished data from the CITF-funded RISC Montreal project, led by Drs. Jedwab and Bignami, showed that:

- Infection-acquired seroprevalence in Montreal North was 12% for the period August to December 2021 – compared to 5% in the rest of Montreal.

- Initial results from baseline surveys suggested that factors contributing to the elevated rate of infection-acquired seroprevalence included: a higher rate of comorbidities, high unemployment (50%), a high percentage of persons working in positions deemed essential (teachers, long-term care and residential facility employees).

- The study also mentioned that, although the sample size is small, immigrants in this cohort had the highest infection-acquired seroprevalence among 18- to 34-year-olds (42%) and amongst those 55+ (33%) (unpublished data).

- In the 35–54-year-old cohort, 42% of immigrants tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 between August 2021 and November 2022, compared to 21% of those who are Canadian citizens by birth. The same trend was found in the 55+ age group, in which 33% of immigrants tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, compared to 18% stating they were Canadian citizens at birth (unpublished data).

- A StatCan report (11) using data from the early waves of the pandemic highlighted that:

- COVID-19 mortality rates were significantly higher for racialized populations (31 deaths per 100,000 population) compared to non-racialized and non-Indigenous populations (22 deaths per 100,000 population). Among different racialized populations Black people had the highest age-standardized COVID-19 mortality rate (49 deaths per 100,000 population), followed by South Asians (31 deaths per 100,000 population) and Chinese (22 deaths per 100,000 population).

- The mortality rate ratio for Black people was more than 2.2 times higher than for the non-racialized and non-Indigenous population. The mortality rate among Chinese people was similar to that of the non-racialized and non-Indigenous population. Furthermore, mortality rates from COVID-19 among those living in low-income neighborhoods were almost 3 times higher than for people living in higher income areas.

Education

During the COVID-19 pandemic, those with less education were more affected.

- A CITF-funded study based in Ontario and led by Drs. Mishra and Kwong further highlighted an increased risk of COVID-19-related deaths in individuals with lower educational attainment (HR- 1.27 for lowest vs. highest proportion with diplomas) (5).

- In other CITF-funded research, Drs. Jedwab and Bignami also found that, among people living in Montreal North aged 18 to 34, those having secondary education or less had a higher infection-acquired seroprevalence rate compared with those who received a CEGEP certificate or higher (23% vs 16%) (unpublished data).

PART 2

How social determinants of health impacted access to vaccines and vaccine uptake in Canada

Vaccine uptake has not been equal across all population groups in Canada. Here, we look at how social determinants of health have shaped access to, and acceptance of, vaccines in a select number of groups, and how to overcome barriers.

South Asians communities

The initial findings from Dr. Anand’s study would suggest that, one year into the pandemic, members of South Asian communities in Canada shared an overall lack of confidence in COVID-19 vaccines:

- According to a survey of close to 1000 South Asian adults living in Peel Region in Ontario, 42.9% received only one dose, while 7.1% received two doses. The remaining 50% were unvaccinated (15). In contrast, 71% of Peel residents had received at least one dose of vaccine, and 59% had received two doses by July 2021 (17).

- The three main sources for COVID-19 related information that members of the community identified as reliable were: healthcare providers and/or provincial public health bodies (63% of those surveyed), followed by traditional media sources such as TV news channels or newspaper (45%), and social media (34%) (15).

- According to a sub-study of 25 South Asians in Ontario and British Columbia, among those who did not trust vaccines, were disinterested, or refused to be vaccinated reported that they did not consider themselves at risk for severe COVID-19 as long as they have a healthy lifestyle and no chronic diseases. Some shared their distrust of publicly shared information about, for example, COVID-19 transmission, deeming it exaggerated (18).

- Most of these participants also reported concerns regarding potential unforeseen adverse effects of vaccines, especially given their rapid development and rollout. Many opposed vaccinating children (18).

Racialized and lower-income area of Montreal North

Preliminary results from Drs. Jedwab and Bignami’s study show that:

- Vaccination with two-doses reached 90% in Montreal North (versus 97% for all of Montreal). However, only 11% of Montreal North residents had received a third dose by June 2022, compared to 52% of other Montrealers.

- However, Montreal North residents were more likely to engage in preventive measures than those living in Montreal, such as limiting contacts with more frail people or self-isolating in the event of experiencing symptoms.

Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside with homelessness and substance abuse, among other issues

Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES) is home to a vulnerable population experiencing high rates of: housing insecurity (including homelessness and living in congregate settings), substance use, and underlying health conditions. For these reasons DTES was prioritized for vaccination starting in January 2021 (19). The CITF-funded project led by Drs. Hudson Reddon, Brittany Barker, and M-J Milloy (British Columbia Centre on Substance Use) looks at the social determinants of vaccination, with a specific focus on people who use unregulated drugs:

- By the end of January 2022, only 64% of DTES residents surveyed reported being vaccinated with a two-dose regimen, compared to 81% in British Columbia as a whole. 9% reported having received a third dose, compared with 45% in the province. 16% were unvaccinated, similar to the provincial rate (14%) (20).

- The most trusted sources of information, as reported in August 2021, were traditional media (as reported by 44% of those surveyed), their personal doctor (24%), other healthcare professionals (21%), and friends (22%) (Unpublished results).

- The most common reasons for vaccine hesitancy were concerns about vaccine side effects (raised by 47% of those undecided or unwilling to get vaccinated), vaccine safety (raised by 26%), not being concerned about getting sick from COVID-19 (12%), and lack of trust in the government (12%) (Unpublished results).

People experiencing homelessness in Toronto

An estimated 235,000 people (representing 0.7% of the population) experience homelessness in Canada (21). Evidence shows that individuals lacking stable, permanent and appropriate housing endure inequalities across a wide range of health conditions (22, 23), which ultimately increase their risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 and having various complications from COVID-19. Also, those who live in congregate settings, such as homeless shelters, are at even higher risk because of crowding, inability to practice physical distancing, and a high population turnover (24). Thus, vaccinating people experiencing homelessness has been a priority across Canada.

The CITF-funded Ku-gaa-gii pimitizi-win study, led by Dr. Stephan Hwang (MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions, University of Toronto), found that uptake of a first dose of vaccine was high among people experiencing homelessness in Toronto, similar to the general adult population (25): by September 2021, 80.4% of the 736 study participants had received at least one dose, compared to 84.3% in the general population at the same time. Vaccine uptake of two or more doses was lower, reaching only 63.6% of the study participants in September 2021 compared to more than 75% among Toronto residents (26).

Some factors that contributed to vaccine hesitancy among adults experiencing homelessness or who are precariously housed in Canada (27):

- Mass vaccination clinics open to the general public were noted to be difficult or unappealing to access for people experiencing precarious housing or homelessness. The main reasons: geographic distance, long wait times, and the necessity to book appointments via internet or phone.

- This population had to prioritize other activities such as finding a place to sleep over getting vaccinated or accessing health services.

- Some were concerned about how to manage potential vaccine side effects without secure housing.

- Access to reliable information that did not come from word of mouth or social media was challenging, with brochures or online resources not perceived useful in this population.

- Greater mental health and substance use challenges could be associated with challenges processing information.

- Stigma and discrimination by healthcare providers have been experienced widely among those experiencing homelessness over time, leading to a growing mistrust with health services, including vaccination.

PART 3

Measures recommended to improve outreach to priority populations most at risk from COVID-19

During the initial waves of the pandemic, public health measures, including testing, mask mandates, quarantine measures, restrictions on public gatherings, and vaccination, were implemented and promoted by officials at the federal, provincial, and local levels. However, it was unclear whether these interventions were reaching communities at high risk. Many communities faced challenges understanding or even receiving information due to language barriers and/or lack of telephone or internet access. Telehealth services, for example, became the norm for booking appointments for medical tests and care, as well as for registering for vaccines, and most communication from health care providers was carried out through email or other messaging systems.

According to Dr. Anand’s CITF-funded study on vaccine confidence among South Asians communities in Toronto and Vancouver, the following measures would help increase vaccine uptake:

- Community advocacy groups should communicate in multiple South Asian languages to raise awareness about the risks of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- Many participants reported the importance of translation and representation in addressing language barriers to vaccination in terms of registration and education (18).

- Consider specific outreach that relies on trusted community members and media, and tailor the approach (18):

- Public health programs with engagement from local influencers (including politicians, celebrities, and athletes) are important in overcoming historical sources of mistrust and addressing cultural-linguistic needs.

- One advocacy group leader pointed out that younger individuals typically use nonethnic media to access information, while older individuals were more likely to access and use ethnic media or their family/friends as valued sources of information.

- Ensure COVID-19 information is consistent across different platforms. Study participants questioned inconsistent COVID-19 mandates and policies seen in different settings and media outlets (18).

Dr. Anand also looked at the impact of the South Asian Youth as Vaccine Agents of Change (SAY-VAC) program (28), which sought to address misinformation and improve vaccine confidence among South Asian youth in the Greater Toronto Area and Hamilton.

- After completing the SAY-VAC programme, participants (30 in total with a mean age of 23) reported an increase in their self-reported knowledge regarding COVID-19 vaccines from 73.3% to 100%. Their self-reported confidence about having a conversation about COVID vaccines with unvaccinated community counterparts increased from 63.6% to 93.1%.

- More than half of participants (51.9%) reported being able to positively affect an unvaccinated community member’s decision to get vaccinated.

Dr. Mishra (5) addressed the importance of improving workplace health and safety protocols, outbreak management, and community-led and community-tailored outreach for testing, effective isolation and quarantine, and vaccine programs.

Dr. Julie Bettinger’s (University of British Columbia) research on public health community engagement with Asian populations in British Columbia (29) also found that targeted and tailored community engagement is necessary to reach diverse communities. In particular, her study shows:

- Participants expressed that knowledge of cultural practices must be integrated with public health strategies to promote better health outcomes.

- Religious centers (such as gurdwaras, mandirs, and mosques) and culturally significant gathering spaces (like local community centers) were key avenues in successfully engaging with community members and delivering public health information and services.

- Structural barriers, including poverty and racialization, were poorly addressed in public health strategies and groups facing these barriers did not have the resources or capacity to advocate for their own health. In-person, low-technology options such as telephone access for vaccine registrations and personalized communication were necessary to reach those facing barriers due to poverty and old age.

- Community engagement with a more familiar, human face, such as trusted community members or leaders and trusted healthcare providers who know the local language and culture are important.

The high vaccination coverage in people experiencing homelessness reported by Dr. Hwang suggests that advocacy and outreach efforts implemented in Toronto to prioritize this population were effective:

- Local agencies regularly interacting with people experiencing homelessness were integrated in the vaccination effort. Among their various initiatives, mobile outreach clinics were deployed to emergency shelters, encampments, and other sites (30, 31)

- Peer ambassadors were also available in outreach clinics to provide information about vaccines (32).

Training healthcare providers already in the community, mostly nurses, has also been important to build trust with people experiencing homelessness (27). Likewise, information on vaccines should be provided by these healthcare providers rather than government or health authorities. Outreach-based vaccination appears to be an effective strategy to increase vaccine uptake and confidence in people experiencing homelessness.

The lead investigator for a CITF-funded study focussing on the Orthodox Jewish community in Quebec, Dr. Peter Nugus (McGill University), recommends that public health pronouncements and mandates consider incorporating negotiation with specific communities to ensure realistic and sustainable compliance; for example, appealing to religious people by linking safety with the desire to attend services on a regular basis.

In conclusion, collaboration is key to disseminating COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination information to at-risk populations. Gaining further insight into strategies for developing relationships with varied communities can help future pandemic planning and disease control efforts in these populations.

Concluding remarks

Research has shown that having lower income, experiencing a high level of material deprivation, being racialized, being an essential worker, or living in a residence with higher bedroom density puts people at increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe outcomes from COVID-19 including hospitalization and death. Similarly, these population groups often have lower rates of vaccination and express high levels of vaccine hesitancy. Efforts to reduce excess risk of infection and disease, as well as to improve vaccine coverage and uptake depend on tailoring interventions to the socio-cultural and economic realities of these diverse communities and moving away from a one-size-fits-all approach. Collaboration with community leaders is key to the effective dissemination of information about COVID-19 and widening acceptance of vaccination.

References

- Zinszer K, Charland K, Pierce L, Saucier A, McKinnon B, Hamelin M-È, et al. Seroprevalence, seroconversion, and seroreversion of infection-induced SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among a cohort of children and adolescents in Montreal, Canada. medRxiv. 2022:2022.10.28.22281660.

- Xia Y, Ma H, Moloney G, Velásquez García HA, Sirski M, Janjua NZ, et al. Geographic concentration of SARS-CoV-2 cases by social determinants of health in metropolitan areas in Canada: a cross-sectional study. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2022;194(6):E195-E204.

- Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). COVID-19 in Ontario: a focus on neighbourhood material deprivation, February 26, 2020 to December 13, 2021. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2022.

- Ma H, Chan AK, Baral SD, Fahim C, Straus S, Sander B, et al. Which curve are we flattening? The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 among economically marginalized communities in Ontario, Canada, was unchanged from wild-type to omicron. medRxiv. 2022:2022.10.24.22281104.

- Wang L, Calzavara A, Baral S, Smylie J, Chan AK, Sander B, et al. Differential Patterns by Area-level Social Determinants of Health in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)–related Mortality and Non–COVID-19 Mortality: A Population-based Study of 11.8 Million People in Ontario, Canada. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2022.

- Government of Quebec. Social inequalities in health: An analysis of links between material deprivation, COVID-19 transmission and associated mortality 2022 [Available from: https://santemontreal.qc.ca/en/public/coronavirus-covid-19/situation-of-the-coronavirus-covid-19-in-montreal/survey-of-the-health/unequal-toll/].

- The Impacts of Socioeconomic Status and Educational Attainment on Youth Success [cited 2022 9/12/2022]. Available from: https://www.pathwaystoeducation.ca/the-impacts-of-socioeconomic-status-and-educational-attainment-on-youth-success/.

- COVID-19 cases and deaths in health care workers in Canada. Canadian Institute of Health Information; 2022 31/03/2022.

- Rao A, Ma H, Moloney G, Kwong JC, Jüni P, Sander B, et al. A disproportionate epidemic: COVID-19 cases and deaths among essential workers in Toronto, Canada. Annals of Epidemiology. 2021;63:63-7.

- Bhatt M, Plint AC, Tang K, Malley R, Huy AP, McGahern C, et al. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from unvaccinated asymptomatic and symptomatic household members with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection: an antibody-surveillance study. CMAJ Open. 2022;10(2):E357-E66.

- Gupta S, Aitken N. COVID-19 mortality among racialized populations in Canada and its association with income. 2022.

- Yang F.J. , Aiten N. People living in apartments and larger households were at higher risk of dying from COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic. StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a better Canada; 2021.

- The Canadian census: A rich portrait of the country’s religious and ethnocultural diversity. Statistics Canada; 2022 2022.10.26

- McKenzie K, Dube S, Petersen S, Equity Inclusion Diversity and Anti-Racism Team from Ontario Health. Tracking COVID-19 Through Race-Based Data. Ontario Health and Wellesley Institute; 2022.

- Anand SS, Arnold C, Bangdiwala SI, Bolotin S, Bowdish D, Chanchlani R, et al. Seropositivity and risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection in a South Asian community in Ontario: a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2022;10(3):E599-E609.

- Montreal’s poorest and most racially diverse neighbourhoods hit hardest by COVID-19, data analysis shows [press release]. 2020.

- COVID-19 in Peel: Dashboard and information about the status of COVID-19 Toronto: Region of Peel2022 [Available from: ttps://www.peelregion.ca/coronavirus/case-status/

- Kandasamy S, Manoharan B, Khan Z, Stennett R, Desai D, Nocos R, et al. Perceptions of COVID-19 risk, vaccine access, and confidence: a qualitative analysis of South Asians in Canada. medRxiv. 2022:2022.10.21.22281321.

- Aggressive vaccination strategy paying off as Vancouver’s DTES achieves ‘significant herd immunity’ [press release]. 2021.

- Lower vaccination rates among people who use drugs could lead to serious outcomes from COVID-19 [press release]. 2022.

- Gaetz S, Dej E, Richter T, Redman M. The State of Homelessness in Canada 2016. Canadian Observatory on Homelessness; 2016.

- Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW, Nordentoft M, Luchenski SA, Hartwell G, et al. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10117):241-50.

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384(9953):1529-40.

- Perri M, Dosani N, Hwang SW. COVID-19 and people experiencing homelessness: challenges and mitigation strategies. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2020;192(26):E716-E9.

- Richard L, Liu M, Jenkinson JIR, Nisenbaum R, Brown M, Pedersen C, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Coverage and Sociodemographic, Behavioural and Housing Factors Associated with Vaccination among People Experiencing Homelessness in Toronto, Canada: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines. 2022;10(8):1245.

- Ipsos & Toronto Public Health COVID-19 Vaccine Survey – Wave 2. Toronto Public Health; 2021 08/2021.

- Supporting COVID-19 vaccine uptake among people experiencing homelessness or precarious housing in Canada. National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health; 2021.

- Kandasamy S, Ariyarajah A, Limbachia J, An D, Lopez L, Manoharan B, et al. South Asian Youth as Vaccine Agents of Change (SAY-VAC): evaluation of a public health programme to mobilise and empower South Asian youth to foster COVID-19 vaccine-related evidence-based dialogue in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, Canada. BMJ Open. 2022;12(9):e061619.

- Pringle W, Sachal SS, Dhutt GS, Kestler M, Dubé È, Bettinger JA. Public health community engagement with Asian populations in British Columbia during COVID-19: towards a culture-centered approach. Can J Public Health. 2022:1-10.

- Casey L. Vaccination of Toronto’s Homeless Well Underway with about 1000 Getting a Shot 2021 [Available from: https://www.cp24.com/news/vaccination-of-toronto-s-homeless-well-underway-with-about-1-000-getting-a-shot-1.5343687?cache=rspnqiqaio%3FclipId%3D89563%3FclipId%3D68597]

- Anselmo A. Community Vaccination Promotion: Increasing Vaccine Confidence and Uptake among Marginalized Individuals and Groups across Canada. 2021 [Available from: https://www.allianceon.org/blog/Community-Vaccination-Promotion-Increasing-vaccine-confidence-and-uptake-among-marginalised]

- City of Toronto. The City of Toronto Continues to Take Significant Action to Assist and Protect People Experiencing Homelessness and Ensure the Safety of the City’s Shelter System 2021 [Available from: https://www.toronto.ca/news/the-city-of-toronto-continues-to-take-significant-action-to-assist-and-protect-people-experiencing-homelessness-and-ensure-the-safety-of-the-citys-shelter-system/]