Frequently Asked Questions

Below you’ll find definitions and answers to the some of the most common questions about COVID-19.

We start with the basics, and answer questions about the virus and the disease itself. Next, we look at immunity and reinfection, COVID-19 vaccines, vaccine surveillance which looks at vaccine effectiveness and safety, and Long COVID. We also break down exactly what seroprevalence and serosurveillance are and why they have been critical to Canada’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We then conclude by answering questions about antibodies, as well as SARS-CoV-2 testing.

If you can’t find what you’re looking for here, reach out to your local public health authority for guidance.

About the virus and disease

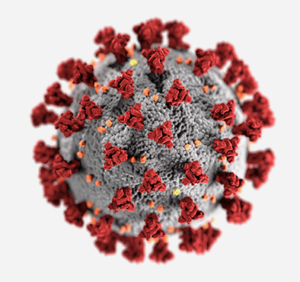

First identified in the 1960s, coronaviruses are a family of respiratory viruses. The name ‘coronavirus’ is derived from the Latin term ‘corona’, meaning “crown.” This refers to the characteristic “crown” shape of the virus’ protein spikes.

There are different kinds of coronaviruses, with some causing disease. Although they usually result in mild to moderate upper respiratory tract infections, there are three which have triggered dangerous epidemics—SARS-CoV (in 2002), MERS-CoV (in 2012), and SARS-CoV-2 (in 2019).

The morphology (shape) of coronavirus is depicted here with spike proteins (red) that form a corona (crown) around the virus. Additional proteins shown include envelope (yellow) and membrane (orange) proteins. Photo Credit: Alissa Eckert, MSMI, Dan Higgins, MAMS.

The morphology (shape) of coronavirus is depicted here with spike proteins (red) that form a corona (crown) around the virus. Additional proteins shown include envelope (yellow) and membrane (orange) proteins. Photo Credit: Alissa Eckert, MSMI, Dan Higgins, MAMS.

SARS-CoV was the virus responsible for the 2002 epidemic which started with influenza-like symptoms but could progress to pneumonia and respiratory failure. The epidemic lasted a few months.

SARS-CoV-2 is more closely related to SARS-CoV than to MERS-CoV, sharing ~80% genomic similarity. However, SARS-CoV-2 can enter human cells more efficiently and includes proteins that have no counterpart in SARS-CoV, so they are not completely alike.

Despite their similarities, the SARS-CoV epidemic ended while vaccines were in early development, so detailed vaccine data was not available in advance of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. However, the foundational biological and clinical lessons learned from both the SARS-CoV and MERS outbreaks were important building blocks for the eventual SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

SARS-CoV-2 stands for ‘severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus’ and is the virus that causes the disease known as COVID-19, or coronavirus disease 2019.

SARS-CoV-2 variants occur when there are changes or mutations in the original virus’ genetic code. Such changes occur over time as a by-product of viral replication. The World Health Organization (WHO) tracks variants of SARS-CoV-2 around the globe and designates them as variants of concern (VOCs) when they spread much faster, are more adept at infecting people, cause more severe disease, and/or reduce the effectiveness of vaccines and therapeutics. In Canada, the Coronavirus Variants Rapid Response Network (CoVaRR-Net) tracks variants and studies which spread faster, are more transmissible, and cause more severe symptoms.

As of March 31, 2024, the WHO had designated five VOCs: Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron. Omicron emerged in November 2021 and spread more quickly than the original SARS-CoV-2 virus and the previous variants. The Omicron variant had more than 50 known mutations by Spring 2024, 32 of which were in the spike protein, allowing for its easy transmission.

The Omicron variant and its first subvariants (BA.1, BA.2, BA.3, BA.4, BA.5) contributed to the massive surge of infections in the Canadian population and other parts of the world starting in early 2022.

The WHO also tracks variants of interest (VOIs), defined as variants with mutations that have the potential to increase transmissibility, disease severity, antibody evasion, reduce susceptibility to therapeutics, and seem to have a growth advantage compared to other circulating variants. As of February 9, 2024, there were five Omicron VOIs: XBB.1.5, XBB.1.16, EG.5, BA.2.86, and JN.1. In March 2024, JN.1 was the most widely circulating variant of SARS-CoV-2. There was no evidence at the time to indicate that it causes more severe disease.

In March 2024, the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 was no longer circulating, and Omicron had become the most widespread variant.

In general, Omicron infections result in fewer hospitalizations, less severe illness, and a higher rate of asymptomatic cases, since it does not tend to infect the lower respiratory tract.

Although Omicron was a less lethal variant of SARS-CoV-2, it caused more deaths across Canada than any other variant due to the very high numbers of people infected. In 2022, COVID-19 was Canada’s third leading cause of death, contributing in large part to the average loss of Canada’s life expectancy by one year.

Symptoms from an infection with Omicron are like those previously reported for COVID-19: fever, cough, sore throat, tiredness, and headache being the most common. Individuals with COVID-19-like symptoms should self-isolate.

On Friday, May 5, 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that COVID-19 was no longer a public health emergency of international concern. However, it remains a global health threat.

The WHO’s decision was based on data which showed that, in the 12 months prior to its decision, the pandemic was on a downward trend, with decreased death rates and reduced pressures on health systems.

However, COVID-19 is still around, and new mutations continue to emerge. It is therefore important to continue getting booster doses and follow public health measures. Although most people are not getting severely ill or dying from the Omicron variant, COVID-19 can still result in death or hospitalizations and should be taken seriously.

Additionally, Long COVID is a major concern for many individuals who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Its full impact on people’s health and on the healthcare system is still being investigated.

The World Health Organization recommends:

- Get vaccinated according to the recommendations of your local health authority as soon as they become available to you

- Avoid crowds and close contact when possible and feasible

- If you can’t avoid crowds or are in a poorly ventilated area, wear a mask

- Wash your hands frequently but especially before touching your eyes or mouth

- When you sneeze, cover your mouth with your elbow or with a tissue

- Self-isolate if you test positive for COVID-19

- Clean and disinfect surfaces that are most frequently touched or accessed (door handles, faucets, phones)

Immunity and reinfection

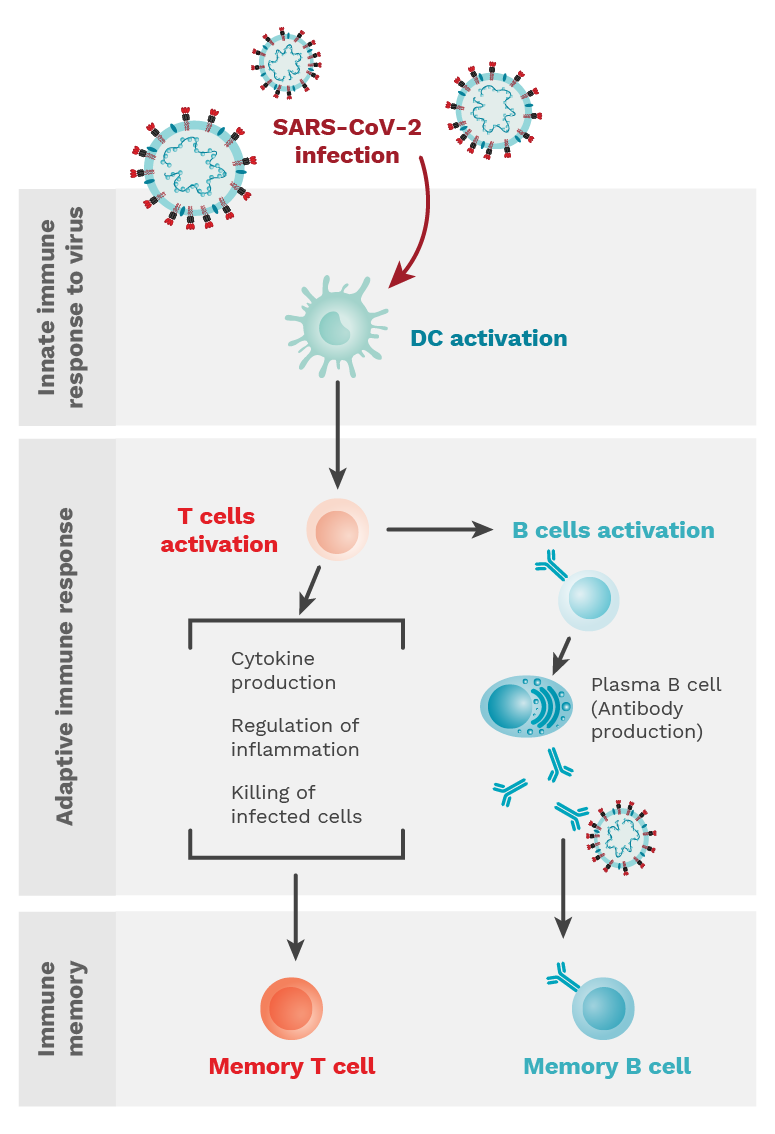

Figure 1.1. When an individual is infected with SARS-CoV-2, the innate immune response is initiated and characterized by dendritic cell (DC) activation. This is followed by an adaptive immune response where T and B cells are activated. T cells can perform many different functions, while B cells differentiate into plasma cells to produce antibodies. Both types of cells establish memory populations to prevent against re-infection. Photo Credit: Mariana Bego.

Infection-acquired immunity is proportional to the severity of the infection. Individuals with severe infection have higher antibody concentrations, and therefore a stronger humoral immune response that could last for months (1, 2). In contrast, individuals with a mild infection are not protected for very long as they have a lower antibody concentration (1, 2).

Protective immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 infection consist of two main mechanisms: humoral immunity (mediated by antibodies) and cellular immunity (mediated by T-cells, among other white blood cells). Overall, studies show that immunity is short-lived and therefore individuals would require a vaccine booster following infection.

By 2024, scientists had found strong evidence that the concentration of IgG antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and the level of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 are “correlates of protection” for vaccines against symptomatic COVID-19 (3).

Humoral immunity (mediated by antibodies):

- Antibody-producing B-cells increase in the first month, and remain high for at least eight months, post-infection (4, 5, 6, 7).

- IgA antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain (RBD), developed in the nose and throat, decrease rapidly after infection. They peak at 16-20 days and start waning one month after infection (8-10), but neutralizing IgA can remain detectable in the saliva for up to 73 days post-infection (10).

- IgG antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike are more durable, and remain detectable, up to 12 months post-infection (11).

- Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 (antibodies that stop the replication of SARS-CoV-2 by affecting how the molecules on the pathogen’s surface can enter cells in the body) and can last up to 10 months post-infection (7).

Cellular immunity (mediated by T-cells, among other white blood cells):

- SARS-CoV-2 also induces cell-mediated immunity by activating SARS-CoV-2 specific CD4 and cytotoxic T-cells; one study found that memory T-cell responses primed by initial viral infection can remain highly cross-reactive for 2 years (12).

References

- Röltgen K, Powell AE, Wirz OF, Stevens BA, Hogan CA, Najeeb J, Hunter M, Wang H, Sahoo MK, Huang C, Yamamoto F, Manohar M, Manalac J, Otrelo-Cardoso AR, Pham TD, Rustagi A, Rogers AJ, Shah NH, Blish CA, Cochran JR, Jardetzky TS, Zehnder JL, Wang TT, Narasimhan B, Gombar S, Tibshirani R, Nadeau KC, Kim PS, Pinsky BA, Boyd SD. Defining the features and duration of antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with disease severity and outcome. Sci Immunol. 2020 Dec 7;5(54):eabe0240. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abe0240.

- He Z, Ren L, Yang J, Guo L, Feng L, Ma C, et al. Seroprevalence and humoral immune durability of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in Wuhan, China: a longitudinal, population-level, cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2021;397(10279):1075-84.

- Gilbert PB, Donis RO, Koup RA, Fong Y, Plotkin SA, Follmann D. A Covid-19 Milestone Attained – A Correlate of Protection for Vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2022 Dec 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2211314.

- Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, Hastie KM, Yu ED, Faliti CE, Grifoni A, Ramirez SI, Haupt S, Frazier A, Nakao C, Rayaprolu V, Rawlings SA, Peters B, Krammer F, Simon V, Saphire EO, Smith DM, Weiskopf D, Sette A, Crotty S. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. 2021 Feb 5;371(6529):eabf4063. doi: 10.1126/science.abf4063.

- Lumley SF, Wei J, O’Donnell D, Stoesser NE, Matthews PC, Howarth A, Hatch SB, Marsden BD, Cox S, James T, Peck LJ, Ritter TG, de Toledo Z, Cornall RJ, Jones EY, Stuart DI, Screaton G, Ebner D, Hoosdally S, Crook DW, Conlon CP, Pouwels KB, Walker AS, Peto TEA, Walker TM, Jeffery K, Eyre DW; Oxford University Hospitals Staff Testing Group. The Duration, Dynamics, and Determinants of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Antibody Responses in Individual Healthcare Workers. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Aug 2;73(3):e699-e709. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab004.

- Cohen KW, Linderman SL, Moodie Z, Czartoski J, Lai L, Mantus G, Norwood C, Nyhoff LE, Edara VV, Floyd K, De Rosa SC, Ahmed H, Whaley R, Patel SN, Prigmore B, Lemos MP, Davis CW, Furth S, O’Keefe JB, Gharpure MP, Gunisetty S, Stephens K, Antia R, Zarnitsyna VI, Stephens DS, Edupuganti S, Rouphael N, Anderson EJ, Mehta AK, Wrammert J, Suthar MS, Ahmed R, McElrath MJ. Longitudinal analysis shows durable and broad immune memory after SARS-CoV-2 infection with persisting antibody responses and memory B and T cells. Cell Rep Med. 2021 Jul 20;2(7):100354. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100354.

- Dulipsingh L, Schaefer EJ, Wakefield D, Williams K, Halilovic A, Crowell R. Comparing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody levels in convalescent unvaccinated, convalescent vaccinated, and naive vaccinated subjects. Heliyon. 2023 Jun;9(6):e17410. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17410. Epub 2023 Jun 17. PMID: 37366522; PMCID: PMC10276490.

- Ma H, Zeng W, He H, Zhao D, Jiang D, Zhou P, Cheng L, Li Y, Ma X, Jin T. Serum IgA, IgM, and IgG responses in COVID-19. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020 Jul;17(7):773-775. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0474-z.

- Beaudoin-Bussières G, Laumaea A, Anand SP, Prévost J, Gasser R, Goyette G, Medjahed H, Perreault J, Tremblay T, Lewin A, Gokool L, Morrisseau C, Bégin P, Tremblay C, Martel-Laferrière V, Kaufmann DE, Richard J, Bazin R, Finzi A. Decline of Humoral Responses against SARS-CoV-2 Spike in Convalescent Individuals. mBio. 2020 Oct 16;11(5):e02590-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02590-20.

- Sterlin D, Mathian A, Miyara M, Mohr A, Anna F, Claër L, Quentric P, Fadlallah J, Devilliers H, Ghillani P, Gunn C, Hockett R, Mudumba S, Guihot A, Luyt CE, Mayaux J, Beurton A, Fourati S, Bruel T, Schwartz O, Lacorte JM, Yssel H, Parizot C, Dorgham K, Charneau P, Amoura Z, Gorochov G. IgA dominates the early neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Jan 20;13(577):eabd2223. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abd2223. Epub 2020 Dec 7. PMID: 33288662; PMCID: PMC7857408.

- Sarjomaa M, Diep LM, Zhang C, Tveten Y, Reiso H, Thilesen C, Nordbø SA, Berg KK, Aaberge I, Pearce N, Kersten H, Vandenbroucke JP, Eikeland R, Fell AKM. SARS-CoV-2 antibody persistence after five and twelve months: A cohort study from South-Eastern Norway. PLoS One. 2022 Aug 10;17(8):e0264667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264667. PMID: 35947589; PMCID: PMC9365168.

- Guo PL, Zhang Q, Gu X, Ren PL, Huang T, Li Y. Durability and cross-reactive immune memory to SARS-CoV-2 in individuals 2 years after recovery from COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet. 2024 Jan;5(1):e24-e33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00255-0.

The short answer is no. Being infected with SARS-CoV-2 does not guarantee that you cannot get re-infected.

However, being previously infected, particularly if symptomatic, does provide some protection from subsequent infections, especially for the ancestral, Alpha, Beta, and Delta variants of SARS-CoV-2. This protective effect has been shown to be significantly lower against the Omicron variant, although protection against developing severe disease or dying upon reinfection remained high. The protection wanes over time but is likely similar to a person who had received two doses of an mRNA vaccine.

There are many factors that affect an individual’s immune response to an infection. Several CITF-funded studies have investigated populations that are particularly vulnerable because they are immune-compromised due to illness (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease or other autoimmune disorders) or are undergoing treatment for other illnesses (e.g., solid organ transplant recipients, cancer patients). In many cases they had more severe disease but not necessarily more immune protection.

Thus, the degree of infection-acquired protection is still an area of active research. According to the data as of spring 2024, vaccinations are the most effective against Omicron.

Like with seasonal coronaviruses that cause the common cold, recovery from an initial infection of SARS-CoV-2 gives a degree of immunity and protection towards reinfection. However, reinfections do occur. In most healthy individuals, reinfections tend to be less severe than the original infection.

There are various factors that influence the impact of a reinfection including the variant that causes the reinfection, the health of the individual (pre-existing conditions/comorbidities), their history of vaccination, their age, how long since their previous infection, and the severity of the first SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The two main reasons for more recent waves of reinfections (as of spring 2024) are newer subvariants and waning immunity.

The Omicron variant, which emerged in November 2021, exhibited increased transmissibility and infectivity, resulting in reinfections becoming more common. Additionally, as time passes post-infection or post-vaccination, antibody immunity begins to wane.

This is why experts currently recommend keeping up to date with vaccinations and taking additional precautions such as frequent hand washing and mask wearing where appropriate (e.g., in crowded areas with reduced ventilation).

A breakthrough infection occurs when individuals who are fully vaccinated against a disease, such as COVID-19, are subsequently infected. The term ‘breakthrough’ signifies that the virus broke through the protective barrier that vaccines provide. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines is not 100% and as such, breakthrough infections can occur, although they are predominantly asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic. COVID-19 vaccines remain the best way to be protected against severe disease, hospitalization, and death resulting from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Hybrid immunity happens when an individual has been vaccinated with two or more doses of the COVID-19 vaccine and has also been infected with SARS-CoV-2, either before or after vaccination. Multiple studies have reported that individuals with hybrid immunity tend to generate more robust immune responses against SARS-CoV-2. This generally refers to increased neutralizing antibody and T cell responses against SARS-CoV-2 antigens, including unique antiviral signatures that are not observed with vaccination alone.

There are several permutations of hybrid immunity, depending on the type of vaccine, the number of vaccine doses, the specific SARS-CoV-2 variant, and the timing of the infection – whether it occurred before or after a person’s last vaccine dose. All these variables affect the levels of antibodies and resulting immune responses.

This is not, however, to imply that one should try to get infected with SARS-CoV-2, as there are risks of severe disease and complications, including post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (also known as Long COVID). Instead, individuals should exercise caution to avoid becoming infected and continue to get booster doses to offset waning immunity.

A summary of specific study results on hybrid immunity:

- During the pre-Omicron period, infection-acquired immunity with vaccination provided more than 90% protection (after two vaccine doses) against reinfection. Protection did not wane more than 1 year after infection or more than six months after vaccination (1).

- During the pre-Omicron period, people with two vaccine doses and a prior infection had a further 66% lower risk of reinfection than those with just infection-acquired immunity (2).

- Previously infected individuals had a slower decline in antibody levels after vaccination than people who had been vaccinated but never infected or infected and never vaccinated (3).

- More recent studies after the spread of Omicron have also shown that hybrid immunity confers strong protection against Omicron infection, and highlight the importance of maintaining booster shots (4).

CITF Page: Research on Hybrid Immunity

- Hall V, Foulkes S, Insalata F, Kirwan P, Saei A, Atti A, Wellington E, Khawam J, Munro K, Cole M, Tranquillini C, Taylor-Kerr A, Hettiarachchi N, Calbraith D, Sajedi N, Milligan I, Themistocleous Y, Corrigan D, Cromey L, Price L, Stewart S, de Lacy E, Norman C, Linley E, Otter AD, Semper A, Hewson J, D’Arcangelo S, Chand M, Brown CS, Brooks T, Islam J, Charlett A, Hopkins S; SIREN Study Group. Protection against SARS-CoV-2 after Covid-19 Vaccination and Previous Infection. N Engl J Med. 2022 Mar 31;386(13):1207-1220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2118691.

- Nordström P, Ballin M, Nordström A. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and COVID-19 hospitalisation in individuals with natural and hybrid immunity: a retrospective, total population cohort study in Sweden. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 Jun;22(6):781-790. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00143-8.

- Nordström P, Ballin M, Nordström A. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and COVID-19 hospitalisation in individuals with natural and hybrid immunity: a retrospective, total population cohort study in Sweden. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 Jun;22(6):781-790. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00143-8.

- Cauchi JP, Dziugyte A, Borg ML, Melillo T, Zahra G, Barbara C, Souness J, Agius S, Calleja N, Gauci C, Vassallo P, Baruch J. Hybrid immunity and protection against infection during the Omicron wave in Malta. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2023 Dec;12(1):e2156814. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2156814. PMID: 36510837; PMCID: PMC9817114.

Although our Seroprevalence in Canada webpage does not specifically show the percentage of Canadians with hybrid immunity, it does show the percentage with infection-acquired antibodies and the percentage with either infection-acquired or vaccine-induced antibodies. As of December 2023, ~81%% of Canadians had infection-acquired antibodies, with most of the infections occurring during the Omicron wave.

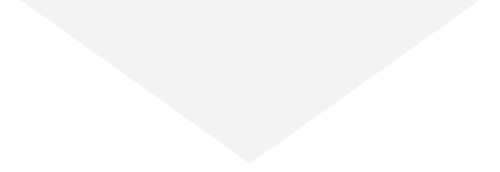

COVID-19 causes diverse degrees of illness, ranging from asymptomatic infection (no apparent symptoms) to more mild symptoms, to severe pneumonia, stroke, sepsis, organ failure, and even death. It is suggested that about 1 in 5 infected people will experience no symptoms, although this number is highly variable depending on the population studied.

It is important to differentiate between asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic infections. Someone who is asymptomatic never develops symptoms, from the time they acquire the virus to the time the infection has fully cleared. Pre-symptomatic refers to someone who will eventually develop symptoms.

Over the course of the pandemic, the incubation period shortened from 7-10 days to 3-4 days.

Although the likelihood of viral transmission is still much higher for symptomatic individuals, asymptomatic infection also plays a role in the spread of COVID-19.

Infection with SARS-CoV-2 can result in a wide range of symptoms such as fever, chills and loss of taste or smell (right panel), or it may go completely unnoticed with no symptoms at all (asymptomatic, left panel). In both cases, infected individuals can go on to transmit the virus to others. Image credit: Kristin Davis.

Current data suggests prior coronavirus infections, including to SARS, may result in the development of antibodies that also fight against SARS-CoV-2, but these antibodies may not be strong enough to fully prevent getting COVID-19. There is evidence to suggest that those individuals previously infected develop an even more robust antibody response against SARS-CoV-2 when vaccinated, compared to those who were not infected in the 2002 epidemic.

However, antibody efficacy can wane, and effectiveness can vary when viruses mutate, so it is always best to follow the most current guidelines from your local health authority. (Figure 1.1)

Cell-mediated immunity (CMI) is the protective immune response generated by immune factors other than antibodies. This includes protection mediated by immune cells such as T lymphocytes (T cells), macrophages, neutrophils, natural killer (NK) cells, and the soluble molecules (cytokines) which are produced by these immune cells.

In addition to generating antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 vaccines also activate cell-mediated immunity.

T cells are an important part of the immune response mounted by our body in response to pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2. There are several subtypes of T cells that respond to different types of pathogens, and they play a critical role in shaping the overall immune response. T cells have proteins on their surface that can detect and kill SARS-CoV-2-infected cells. They can also release a wide range of small soluble molecules (cytokines) that can recruit other immune cells to help clear the infection. T cells also influence the antibody response against SARS-CoV-2 by shaping the type of antibodies generated against the virus. Finally, once the infection is cleared, T cells establish themselves as a small memory population that is pre-primed and ready to react to any future re-exposure to SARS-CoV-2, thus protecting against any subsequent infection that may occur.

In addition to cell-mediated immunity, antibody-mediated immunity is also a critical arm of the protective immune response. Antibody-mediated immunity, also referred to as humoral immunity, involves macromolecules. These include complement proteins, antimicrobial peptides, and secreted antibodies. Humoral immunity is primarily driven by B cells which are the cells that produce antibodies.

COVID-19 vaccines have been shown to activate antibody-mediated immunity and help generate antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

After receiving a vaccine against COVID-19 or recovering from a SARS-CoV-2 infection, the immune system remains “primed” for exposure or re-exposure to the virus. Immune cells that have recognized and resolved the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, or in the case of a vaccine, recognized the parts of the SARS-CoV-2 virus included in the vaccine formula, establish long-living memory cell populations which are ready to react quickly to a virus.

One long-term analysis found that waning of the antibody response post-vaccination is characterized by two features:

- An initial rapid decay after the peak response

- A stabilized slower decay, suggesting antibodies can be long lasting

This study suggests that it’s likely not waning antibody immunity, but the virus mutating to evade the immune system that is causing most new infections in vaccinated populations.

Data (Sept 2023-Jan 2024) by the CDC suggests that the COVID-19 vaccines available were effective against the newer Omicron variants, including JN.1.

COVID-19 vaccines

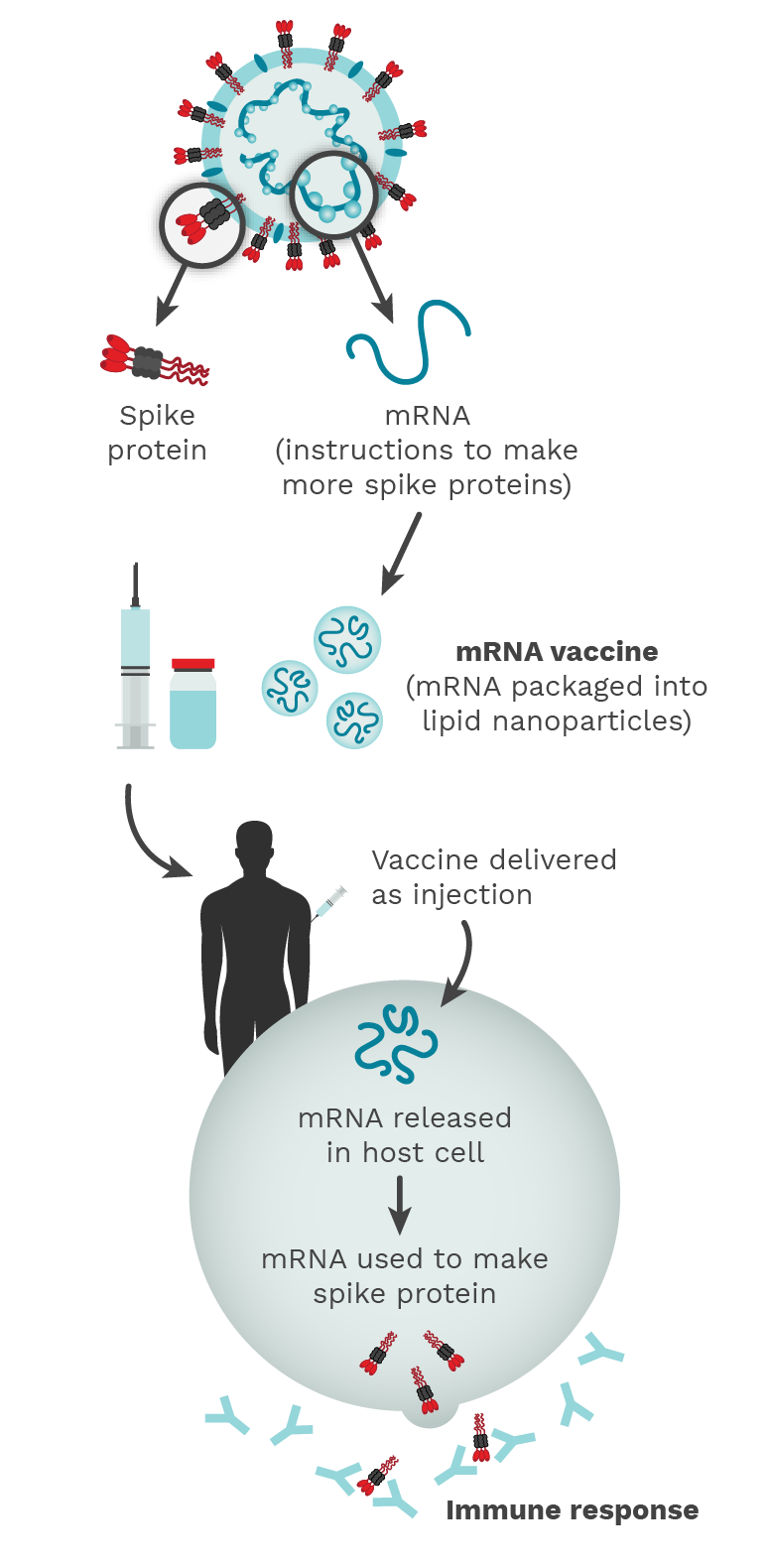

Figure 2.1. The COVID-19 mRNA vaccine contains instructions (mRNA) to make a lot of SARS-CoV-2 Spike proteins. The release of this Spike protein outside of the host cell triggers an immune response and the host makes antibodies, B cells, and T cells against the virus, similar to what happens in natural infection. Photo Credit: Mariana Bego.

Vaccine-induced immunity tends to wane over time, so it is important to get COVID-19 booster doses. The National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) updates its recommendations a few times a year. At time of writing, they had updated their recommendations in May 2024, suggesting every Canadian over 6 months of age get a booster with the latest selected strain in fall 2024. See their guidance for fall 2024 here.

There are 2 types of vaccines currently approved for COVID-19 in Canada.

- mRNA vaccines

mRNA based vaccines, such as the ones created by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna Spikevax, contain mRNA that codes for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. At the beginning of the pandemic, this was done for the original SARS-CoV-2 strain, but since then, the chosen mRNA has been geared to proteins from the more recent variants of concern.

Through vaccination, the mRNA gets delivered to your cells which is then able to produce the viral protein and engage the immune system, priming it to be able to rapidly recognize the live virus at the time of exposure. Matrix-M is a novel saponin-based adjuvant that facilitates activation of the cells of the innate immune system, which enhances the magnitude of the spike protein-specific immune response.

- Protein subunit vaccines

Protein subunit vaccines, such as the Novavax vaccines, consist of harmless proteins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, more specifically, a purified full-length SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike protein nanoparticle co-formulated with the adjuvant Matrix-M.

All types of vaccines have the same end goal: generate a supply of memory B and T cells to remember how to the fight the virus in the future. (Figure 2.1)

There are several COVID-19 vaccines that are approved and authorized for use in Canada (see table below). This information has been obtained from the Government of Canada, whose webpage includes more details on timing between doses, the dose volumes, and specific recommendations for immunocompromised populations. This table was last updated in March 2024.

| Brand name | Manufacturer(s) | Research name | Vaccine type | Available

doses |

Approved for |

| Comirnaty® Omicron XBB.1.5 | Pfizer and BioNTech Manufacturing GmbH | Raxtozinameran | mRNA vaccine

(mRNA against the spike protein of the Omicron XBB.1.5 variant) |

3 mcg

10 mcg 30 mcg |

6 months to < 5 years (3 mcg)

5 to 11 years (10 mcg) 12 and older (30 mcg) |

| Comirnaty® Original and Omicron BA.4/BA.5 | Pfizer and BioNTech Manufacturing GmbH | Tozinameran/Famtozinameran, Bivalent | mRNA vaccine, bivalent

(half the mRNA encodes for the spike protein of the original strain, the other half for the Omicron BA.4/5 variants) |

10 mcg

30 mcg |

6 months to 4 years (3 mcg)

5 to 11 years (10 mcg) 12 and older (30 mcg) |

| Spikevax® XBB.1.5 | Moderna | Andusomeran | mRNA vaccine

(mRNA against the spike protein of the XBB.1.5 variant) |

25 mcg

50 mcg |

6 months to 11 years (25 mcg)

12 and older (50 mcg) |

| NuvaxovidTM | Novavax | N/A | Protein subunit vaccine (against the spike protein of the original strain) | 5 mcg | 12 and older

18 and older (as a booster) |

| Nuvaxovid XBB.1.5 | Novavax | N/A | Protein subunit vaccine (Recombinant XBB.1.5 spike protein pre-mixed with Matrix M) | 5 mcg | 12 and older |

In addition to these vaccines, monoclonal antibody therapies have also been authorized for pre-exposure prophylaxis of COVID-19:

EVUSHELD™ (tixagevimab and cilgavimab), AstraZeneca Canada Inc. Authorized for use in those 12 years of age and older weighing at least 40 kg (300 mcg of tixagevimab and 300 mcg of cilgavimab administered in sequence).

As COVID-19 vaccine recommendations vary by province, visit the following provincial websites for more information.

British Columbia: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/covid-19/vaccine/plan

Alberta: https://www.alberta.ca/covid19-vaccine.aspx

Manitoba: https://www.gov.mb.ca/covid19/vaccine.html

Ontario: https://www.ontario.ca/page/covid-19-vaccines#booster-doses

Québec: https://www.quebec.ca/en/health/advice-and-prevention/vaccination/covid-19-vaccine#c84759

New Brunswick: https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/corporate/promo/covid-19/nb-vaccine.html

Nova Scotia: https://www.nshealth.ca/coronavirusvaccine

Prince Edward Island: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/information/health-and-wellness/getting-the-covid-19-vaccine

Newfoundland and Labrador: https://www.gov.nl.ca/covid-19/vaccine/gettheshot/#second-booster

Nunavut: https://www.gov.nu.ca/health/information/covid-19-vaccination

Northwest Territories: https://www.nthssa.ca/en/services/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-updates/covid-vaccine

Yukon: https://yukon.ca/en/vaccine-questions#booster-vaccines

To get emergency approval, as was the case for the COVID-19 vaccines, pharmaceutical companies needed to show the vaccines were safe and effective, but not necessarily that they would also prevent transmission.

Despite transmission prevention not being a requirement for COVID-19 vaccine approval, it has since been shown that vaccinations do help prevent viral transmission. Although the initial SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were able to prevent transmission quite effectively, the virus mutated and became more immune evasive (meaning it was increasingly difficult for vaccines (or previous infections) to stop transmission. That said, the vaccines have proven very effective at preventing severe disease and death, which are the most important functions for vaccines, making an enormous impact on public health.

As transmission still occurs, however, it remains important to stay home if feeling unwell and wear a mask if sick and needing to go out, so as not to spread the virus to others.

At this time, vaccines are approved, available, and recommended for children starting at 6 months to 5 years, as well as 5 and older.

Both the original mRNA vaccines and Novavax Nuvaxovid original have been associated with a rare risk of myocarditis/pericarditis. Data is not yet available for XBB.1.5 vaccines.

However, in data that has been collected from previous rounds of vaccinations, cases of myocarditis/pericarditis have been rare. The Government of Canada has also stated that, “Evidence from bivalent and original mRNA COVID-19 vaccines across different age groups show that the risk of myocarditis is lower following boosters compared to dose 2 of the primary series, and that no product-specific difference in the risk of myocarditis has been identified following a booster dose at this time, including in adolescents 12 to 17 years of age.”

It’s also important to note that the incidence of myocarditis and pericarditis has been shown to be higher in those who are unvaccinated compared to those who have been vaccinated.

More information on seroprevalence and effects of COVID-19 on children and adolescents can be found in this CITF Secretariat research synthesis.

SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy is associated with increased risk of hospitalization, ICU admission, preterm birth, low birth weight, and NICU admission. Vaccination during pregnancy does not increase risk for adverse pregnancy/birth outcomes, including miscarriage, stillbirth, low birth weight, preterm birth and NICU admission. Actually, vaccination helps lower these risks.

Pregnant individuals are particularly recommended to get vaccinated, preferably with an mRNA vaccine, since there is more available data on this type of vaccine’s safety in this population. One can be vaccinated at any stage of pregnancy.

Rates of vaccine-related adverse effects have been shown to be similar in people who are pregnant or breastfeeding and those who are not pregnant or breastfeeding. Studies have not found any impacts of mRNA COVID-19 vaccination on the infant/child being fed human milk or on milk production or excretion.

There is a Canadian COVID-19 Vaccine Registry for Pregnant and Lactating Individuals, hosted at the University of British Columbia and supported by the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force (CITF) to assess the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines.

Read more about vaccination during pregnancy in this CITF Secretariat research synthesis.

A third vaccine dose was found to improve immunity in many patients with immune mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID) (1-3). The effectiveness of vaccination and the immune responses elicited in IMID patients depend on factors including their age, comorbidities, and immunomodulatory treatments. In partially or fully vaccinated transplant recipients with Omicron infection, their immune responses were comparable to people with healthy immune systems who had been vaccinated three times (this did depend on their age and the treatments they were receiving) (4). This suggests that COVID-19 vaccinations elicit strong protective immunity in immunocompromised individuals (4).

The CITF has funded multiple studies looking at vaccine safety and effectiveness in people with HIV, IMIDs such as inflammatory bowel disease and inflammatory arthritis, chronic kidney disease, recipients of solid organ transplants, and people living with or being treated for cancer. Read more on the findings from this CITF-funded research in this CITF Secretariat research synthesis here.

- Cheung MW, Dayam RM, Law JC, Goetgebuer RL, Chao GYC, Finkelstein N, Stempak JM, Pereira D, Croitoru D, Acheampong L, Rizwan S, Lee JD, Ganatra D, Law R, Delgado-Brand M, Mailhot G, Piguet V, Silverberg MS, Watts TH, Gingras A-C, Chandran V. Third dose corrects waning immunity to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in immunocompromised patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. RMD Open. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002622.

- Quan J, Ma C, Panaccione R, Hracs L, Sharifi N, Herauf M, Makovinović A, Coward S, Windsor JW, Caplan L, Ingram RJM, Kanji JN, Tipples G, Holodinsky JK, Bernstein CN, Mahoney DJ, Bernatsky S, Benchimol EI, Kaplan GG; STOP COVID-19 in IBD Research Group. Serological responses to three doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2023 Apr;72(4):802-804. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327440.

- Windsor JW, Caplan L, Ingram RJM, Charlton C, Kanji JN, Tipples G, Holodinsky JK, Bernstein CN, Mahoney DJ, Bernatsky S, Benchimol EI, Kaplan GG; STOP COVID-19 in IBD Research Group. Serological responses to the first four doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Oct 25:S2468-1253(22)00340-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00340-5.

- Ferreira VH, Solera JT, Hu Q, Hall VG, Arbol BG, Rod Hardy W, Samson R, Marinelli T, Ierullo M, Virk AK, Kurtesi A, Mavandadnejad F, Majchrzak-Kita B, Kulasingam V, Gingras AC, Kumar D, Humar A. Homotypic and heterotypic immune responses to Omicron variant in immunocompromised patients in diverse clinical settings. Nat Commun. 2022 Aug 4;13(1):4489. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32235-x.

Yes, even if you have previously had COVID-19, you should still get vaccinated as the strength of the infection-acquired immune response can vary and will wane over time. Additionally, getting vaccinated can actually boost your immunity even more compared to those who are vaccinated but had not been previously infected.

As of March 2024, it is safe to assume most individuals have been exposed to COVID-19. As such, the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI), which updates its recommendations a few times a year, recommends every Canadian over 6 months of age get a booster with the latest selected strain in fall 2024. See their guidance for fall 2024 here.

Those who have had a SARS-CoV-2 infection can wait 6 months after their infection to get the booster, although a minimum of 3 months has also been shown to be an effective interval.

Vaccination is one of the best tools to limit severe disease.

Vaccine surveillance

Vaccine surveillance studies look at vaccine effectiveness (how good are vaccines at preventing severe disease, new infections, and transmission) and vaccine safety (identifying and quantifying the vaccine’s adverse effects). An adverse effect is an undesired harmful effect resulting from a medication or other intervention.

Vaccine surveillance also looks more precisely at the immune response generated by the vaccine: how successful is the vaccine at developing a protective immune response; what are the details of the vaccine-induced immune response; how long can these “markers of protection” be detected; how long will the vaccine work.

Vaccine surveillance covers vaccine confidence which explores the driving factors behind any concerns people may have about getting vaccinated (also known as vaccine hesitancy).

Vaccine effectiveness is measured by the impact of vaccination on COVID-19-related hospitalizations and deaths, the effects of COVID-19 vaccination on asymptomatic infection and transmission, and how groups of different ages, and overall health status, respond to the vaccine.

Some of the studies the CITF supported include assessing effectiveness with different combinations of vaccines, vaccinations in pregnant women and children, vaccinations in people at higher risk due to other health conditions, and vaccine effectiveness for prevention of serious outcomes among hospitalized adults.

Read lay summaries of CITF-funded research results relating to vaccine safety and effectiveness.

The CITF supported several research studies which evaluated vaccine safety. Vaccine safety is evaluated by tracking adverse events following immunization (AEFIs) including an association with anaphylaxis and other allergic events, Guillain-Barré syndrome, Bell’s palsy, and vaccine-associated enhanced disease, among others.

Some CITF-funded studies document health events including temporary local injection site reactions, systemic symptoms (fever, fatigue, myalgia), respiratory symptoms suggestive of the cold or flu, and gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or stomach pain), among others. The populations studied overlap with studies measuring vaccine effectiveness and include pregnant women, children, people at higher risk due to other health conditions, and hospitalized adults.

Read lay summaries of CITF-funded research results relating to vaccine safety and effectiveness.

Long COVID

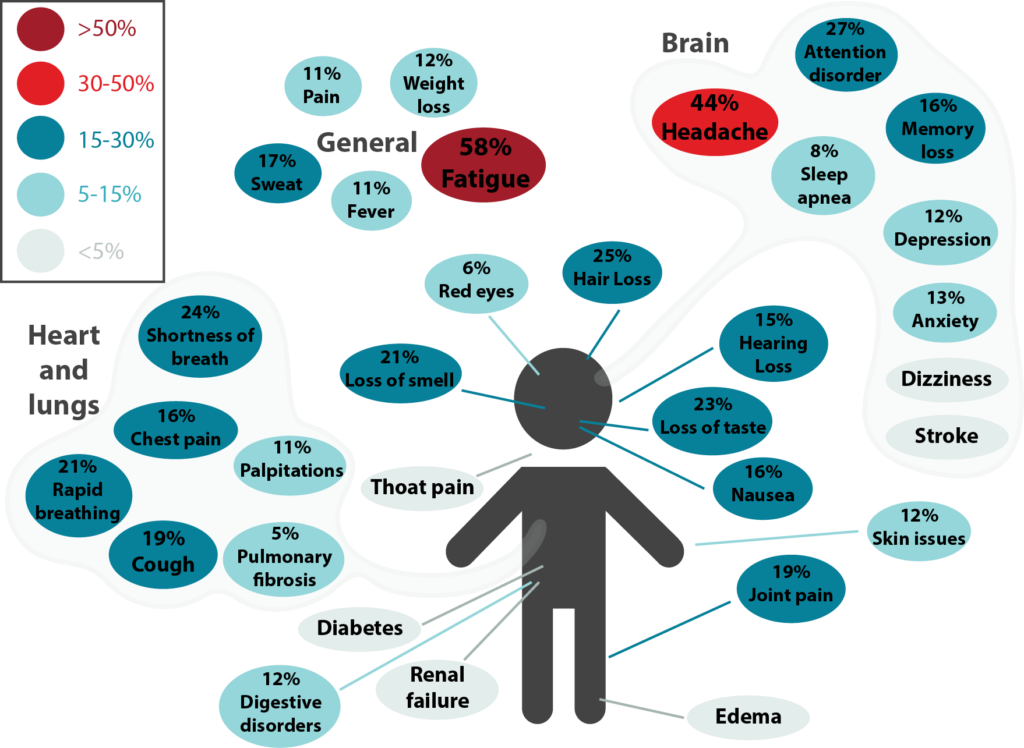

Figure 3.1. Long-term effects of COVID-19. This was adapted from a meta-analysis by Lopez-Leon et al. and it shows the percentage for each long-term symptom of COVID-19. Symptoms were categorized under general, brain, and heart and lungs. The most common symptoms were fatigue, headache, attention disorder, hair loss, and shortness of breath.

Long COVID, also known as post-COVID conditions (PCC), refers to the wide range of symptoms and conditions that some people experience four or more weeks after an initial infection by SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The World Health Organization defines PCC as “symptoms and medical complications that persist, return, or emerge 12 weeks after the initial acute infection phase.” (Figure 3.1)

Long COVID is an umbrella term that refers to a group of disorders that can develop after SARS-CoV-2 infection. For people to be considered as having Long COVID, symptoms must be new (after infection), persistent or recurring over weeks, months, even years. They include respiratory, neurological, psychological, and cardiac issues. Common symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive dysfunction, or “brain fog”. Symptoms may start following a recovery from COVID-19 or persist from the initial illness. Symptoms may also fluctuate or relapse over time. These symptoms can significantly interfere with the day-to-day lives of some individuals, preventing them from doing daily activities or walking short distances.

While Long COVID most often occurs in those who experienced a severe COVID-19 infection, it is not limited to that group of people. Other at-risk groups include the unvaccinated, the female sex, smokers, those with underlying health conditions, and older people, especially those who are frail.

As of March 2024, it’s believed that ~17% of patients with COVID-19 will develop Long COVID.

Research into what causes Long COVID is ongoing and includes the potential reactivation of latent virus, an autoimmune response, organ damage, or remnants of live virus remaining in the tissues. According to the Director of the National Institute of Health, Dr. Monica Bertagnolli, evidence as of spring 2024 suggested vaccinations play a key role in preventing Long-COVID.

The CITF funded a few studies on long COVID, including one by Statistics Canada called the Canadian COVID-19 Antibody and Health Survey cycle 2 (CCHAS-2).

Read a CITF Secretariat research synthesis on Long COVID from February 2022.

See individual results of CITF-funded research Long COVID.

Seroprevalence and serosurveillance

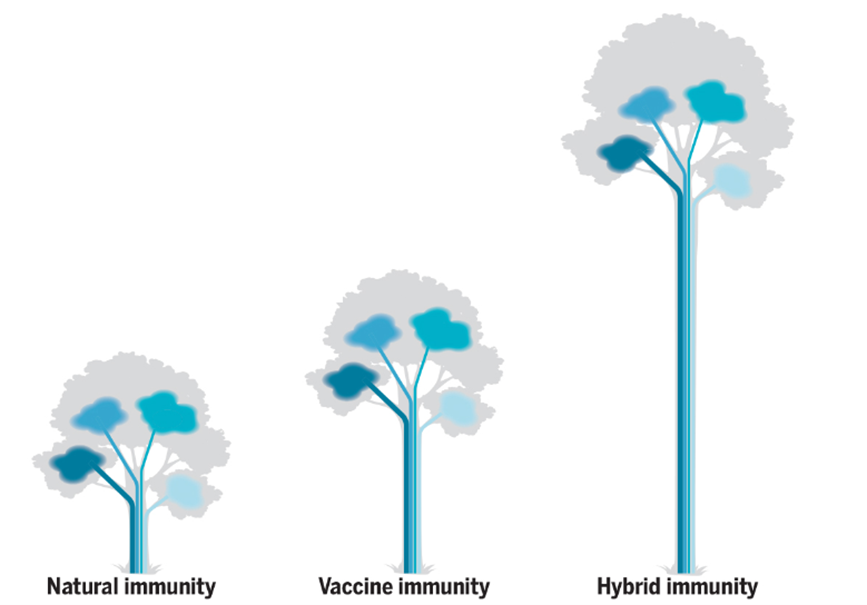

Figure 4.1. A visual representation of hybrid immunity as seen in plants; known as ‘hybrid vigor,’ it is when different plant lines are bred together, and the hybrid is a much stronger plant. Something similar happens when natural immunity is combined with vaccine-generated immunity, resulting in 25 to 100 times higher antibody responses, driven by memory B cells and CD4+ T cells and broader cross-protection from variants (1).

- Shane Crotty. Hybrid immunity. Science. 2021; 372,1392-1393. doi: 10. 1126/science.abj2258.

Seroprevalence is the number (or percentage) of people in a population who test positive for specific antibodies against a virus or infectious agent, based on blood tests. For example, if seroprevalence is 1%, then 1% of the population studied has antibodies to the virus or infectious agent. The detected antibodies could be due to a previous infection and/or due to vaccination.

Serosurveillance provides estimates for antibody levels (in blood samples) against infectious agents, such as SARS-CoV-2 in a large group of people.

It is the gold standard for measuring population immunity from infections or vaccinations. Effective serosurveillance, in conjunction with other key epidemiological data like hospitalizations, mortality rates, and immunization coverage, helps public health officials craft reasonable public health guidelines. When it’s known how many people have antibodies to ward off potential infection, or at least serious forms of infection, public health officials can more confidently inform and protect people.

To understand population immunity to SARS-CoV-2, blood samples from tens of thousands of Canadians were tested to check levels of antibodies directed against SARS-CoV-2 proteins and the CITF amalgamated the data. Each month, the CITF would send a report to Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer and update its Seroprevalence in Canada webpage with the latest seroprevalence estimates.

“Natural” immunity, which we prefer to call infection-acquired immunity, refers to the defense developed against SARS-CoV-2 due to an infection or exposure – not due to a vaccine.

Vaccine-induced immunity refers to the body’s defense mechanism against a virus created in response to a vaccine.

Hybrid immunity, as the name suggests, refers to a combination of infection-acquired and vaccine-induced immunity, and tends to be present a larger immune response.

Data is still being gathered on how long each of these immunities, or their combinations, last. There are many factors that impact the strength of an individual’s immune response.

Understanding antibodies

When our bodies detect the presence of a foreign or ‘never before seen’ protein, like a viral protein, we make antibodies. Antibodies are specific proteins produced by the immune system to recognize and bind to those “foreign” substances (antigens) and eliminate them from the body.

This process is part of a healthy immune response and is the basis for the protective effect of vaccines. Antibodies can be detected in the blood of people who have been recently infected and vaccinated. In many cases, they are detected long after the initial exposure.

Another name for antibodies is immunoglobulins, shortened to Ig, and they come in a variety of subtypes: IgA, IgM, IgG, IgE, and IgD. Of these, IgM is the first to be made in response to a foreign protein and it can be found in blood for a short time after exposure to the antigen. IgG antibodies appear a little later but can be detected for longer. Vaccines designed against COVID-19 approved and authorized for use in Canada primarily produce IgG antibodies recognizing the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 variants and subvariants.

Antibody binding is highly specific. Antibodies cannot bind to just any protein – only their target. The strength and specificity of their binding is the basis for many of their important roles: they can alert several branches of the immune system of an ongoing infection, and they can mark foreign proteins (and consequently the virus attached to them) to be ingested by immune cells and destroyed.

A unique type of antibody called a neutralizing antibody recognizes foreign proteins and prevents them from binding to cell receptors, thereby blocking the virus’ entry into human cells. For SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, the spike (S) protein is what gets targeted.

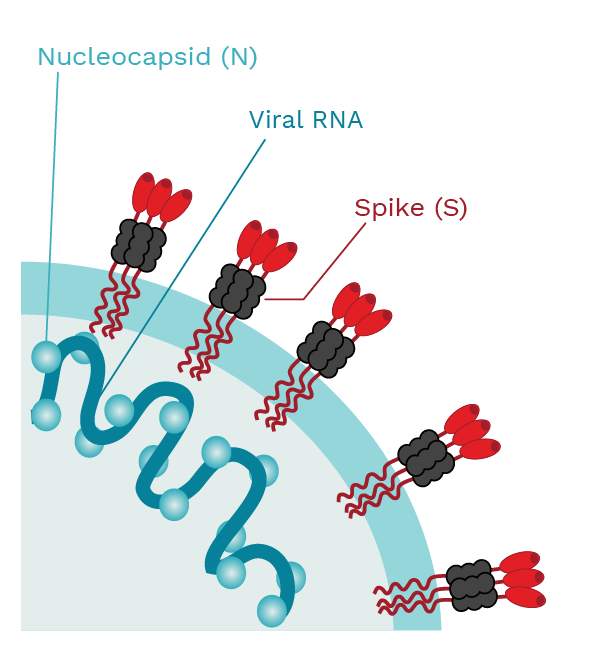

Spike (S) proteins make up the outer layer of the virus. They are what give the virions (the viral infectious particles) the appearance of having a crown. Spike proteins are responsible for binding to the cellular receptor, an event required for the virus to enter the human cell. COVID-19 vaccines were designed against the S protein.

The COVID-19 vaccines available in Canada and most other countries were designed against the S protein. Antibodies recognizing the S protein are dubbed anti-spike IgG. Likewise, antibodies recognizing the N protein are named anti-nucleocapsid IgG and their detection is suggestive of a previous infection with SARS-CoV-2 as vaccination will only produce anti-S IgG.

|

SARS-CoV-2 has the spike (S) proteins that cover the outer membrane surface. These S proteins bind to a receptor called the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). The nucleocapsid (N) protein forms complexes with the viral RNA and is involved in viral replication. Photo Credit: Mariana Bego |

SARS-CoV-2 testing

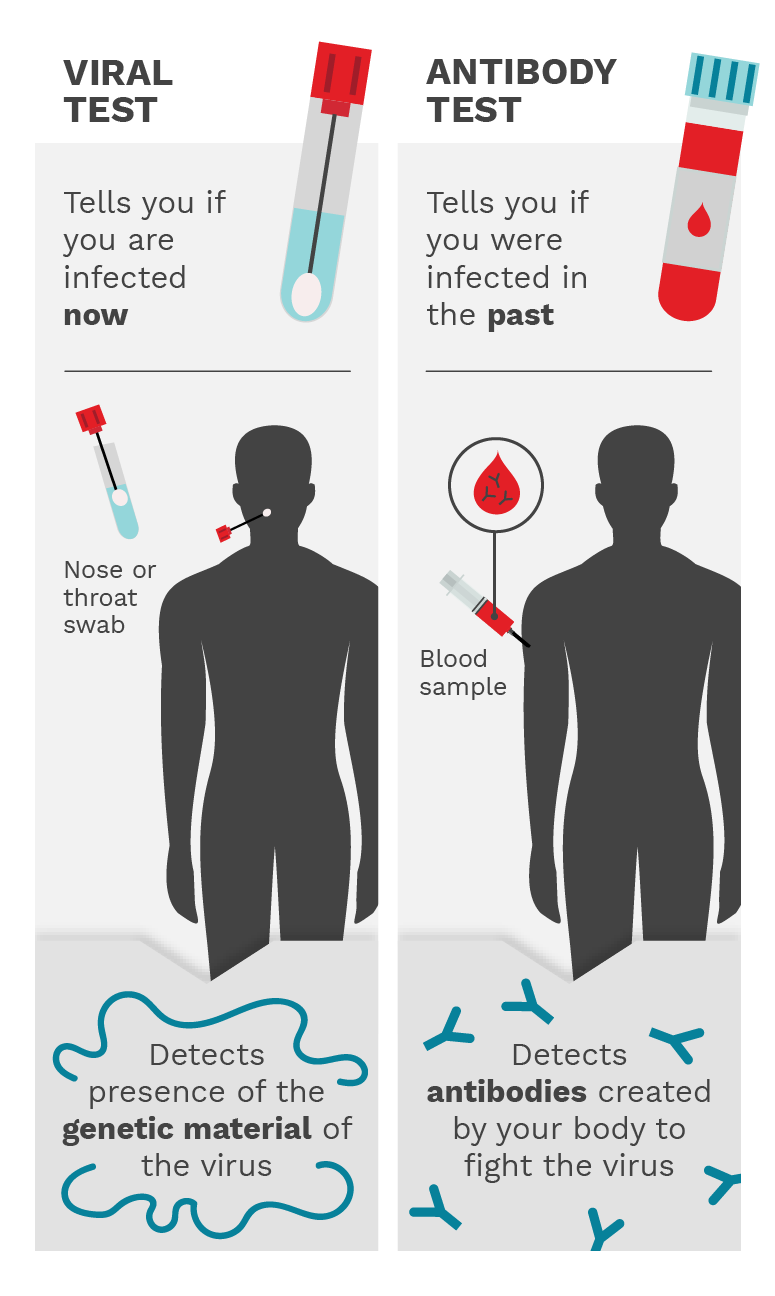

Figure 5.1. The viral test involves a nose or throat swab and it detects the presence of the genetic material of the virus, telling you if you have an active infection. The antibody test involves a blood sample and it detects the antibodies created by your body to fight the virus. This tells you if you were infected in the past. Photo Credit: Mariana Bego

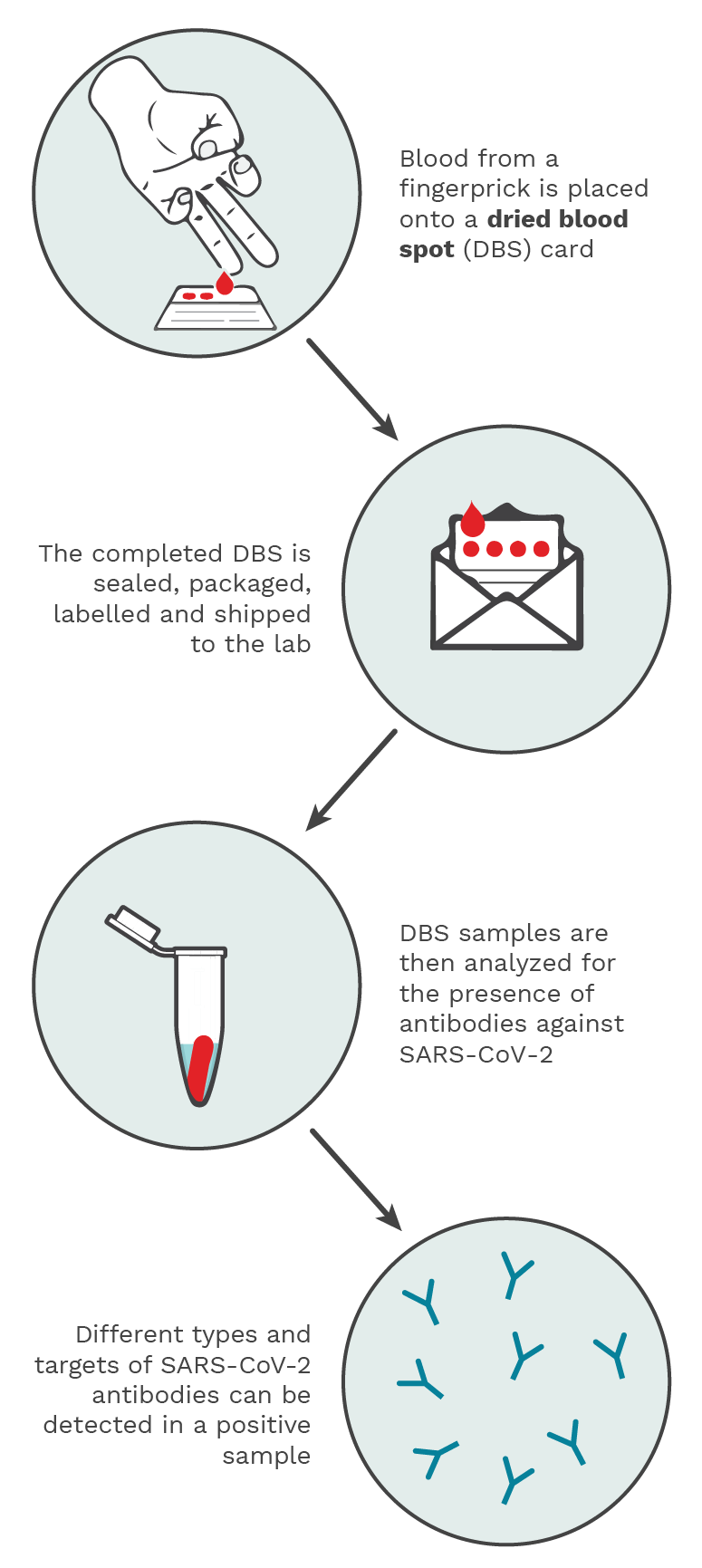

Figure 5.2. Using a spring-loaded lancet provided in the test kit, drops of blood from a fingerprick are placed onto the DBS filter paper card. The DBS is then sealed, packaged, labelled and shipped to an analytical lab, where it is processed and analyzed for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. A positive result would be indicative of a past infection. Photo Credit: Kristin Davis.

Watch an explanatory VIDEO.

A viral test, also known as a diagnostic test, can tell you if you have an active SARS-CoV-2 infection, which would require you to take steps to isolate yourself to prevent infecting others.

The test is often performed with samples obtained from a nose or throat swab, as these areas are most likely to have enough virus to be detected. A positive test indicates an active infection. Saliva testing is also an option. Once the infection resolves, the test would yield a negative result.

More specifically, the test itself looks for the presence of the virus’ genetic material. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, this genetic material is RNA.

Obtaining a negative result from a throat or nose swab or a saliva test (viral test) does not imply that a person has never had COVID-19. It means that the person is not infected with the virus currently, or that the virus is no longer present in the nose or throat mucus, or that there is so little of the virus present that it cannot be detected by the test.

A viral test can tell you if you are currently infected with SARS-CoV-2, while an antibody test can tell you if you have had an infection or responded to a vaccination in the past by making antibodies against the viral proteins. Antibody testing can be used to differentiate between infection-acquired and vaccine-induced immunity. For example, someone previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 will have antibodies recognizing viral proteins (often tested as antibodies recognizing the viral proteins spike and nucleocapsid), whereas someone who received a COVID-19 vaccine will only have antibodies recognizing spike, but not nucleocapsid. The latter is because COVID-19 vaccines available in North America were designed using only the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. (Figure 5.1)

PCR tests can determine an active infection by identifying the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2 (RNA) with a nasal or throat swab or a saliva sample. One usually needs to get a PCR test done by a health professional as they are tested in a laboratory.

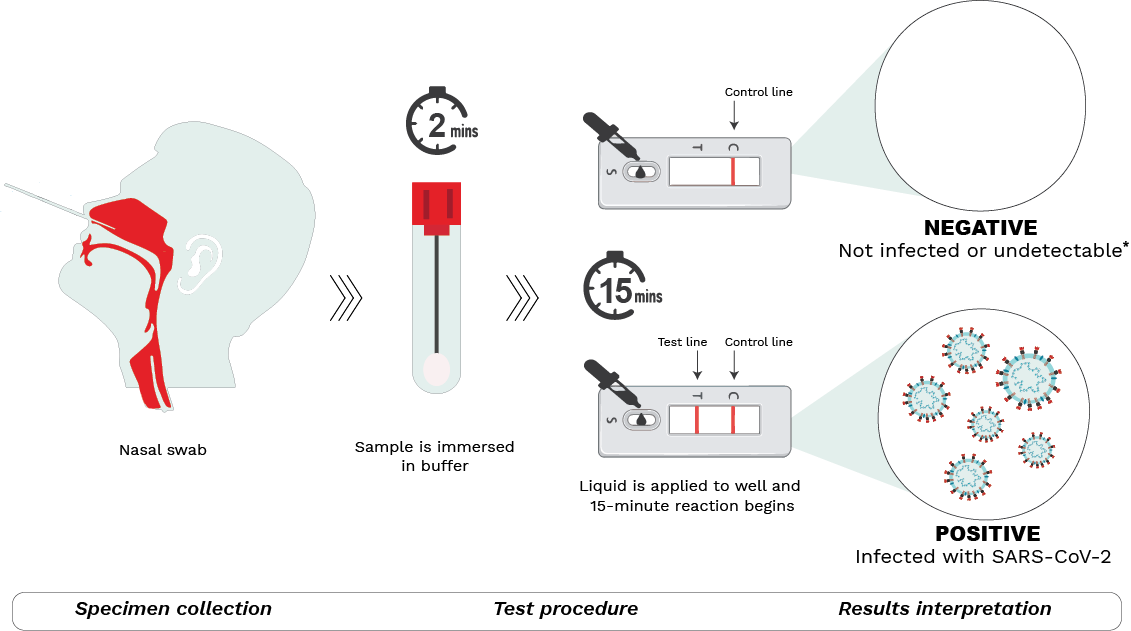

Antigen tests can determine an active infection (less sensitive than a PCR test) by identifying the presence of SARS-CoV-2 protein pieces with a nasal or throat swab. Home antigen tests were developed over the course of the pandemic, and these were most often done at home.

Antibody (serology) tests can determine a past infection by identifying antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 with a blood sample. These blood samples can be taken via a needle (usually at a hospital, clinic or blood drive) or via a dried blood spot test (which was developed during the pandemic with the help of the CITF to be able to allow people to take blood samples themselves at home). (Figure 5.2)

At-home rapid antigen tests for COVID-19 have become more commonplace in the absence of widespread PCR testing. They are called antigen tests because they detect antigens, specific proteins that make-up the SARS-CoV-2 virus, instead of detecting genetic material (RNA) as PCR tests do. Further, they provide test results in less than an hour, hence the designation ‘rapid’.

A rapid antigen test’s sensitivity, defined as its ability to detect the virus when present, is dependent on an individual’s viral load. Viral loads – the amount of virus in nasopharyngeal fluids and blood – are higher early on in infection when the virus is replicating exponentially. Viral loads are mostly detectable during the first five days of symptoms. After this initial period, rapid antigen test performance decreases quickly as viral loads decline and the infection clears.

Rapid antigen tests detect current infections, including those caused by Omicron. They cannot, however, tell whether an individual has had a previous infection with SARS-CoV-2. Vaccination against COVID-19 does not interfere with the test’s ability to detect a current infection.

Schematic depiction of the COVID-19 rapid antigen tests available in Canada.

Step 1 – Specimen collection

A nasal sample is collected using the sterile swab provided. Blowing the nose prior to swabbing, tilting the head back 70 degrees, compressing the nostril with the aid of fingers, and using circular motions while in the nasal cavity have been known to aid with collection.

Step 2 – Test procedure

The swab is submerged in a buffer solution to extract the SARS-CoV-2 virus (if present). After a rest period, the resulting liquid is dispensed with the aid of a nozzle into the sample well on the testing device. The sample then moves through the testing device during which antigens present in the sample bind to antibodies in the device, forming antigen-antibody complexes. The reaction lasts for 15-30 minutes (depending on the manufacturer’s instructions) after which results may be read.

Step 3 – Results interpretation

Two lines detected at the T (test) and C (control) lines of the test window indicate a positive result. This means the sample is positive for SARS-CoV-2 and the person is most likely infected. If only one line at C (control) appears, the result is negative, meaning that the individual is most likely not infected.

It is important to note that a negative result may also indicate that a person is infected but below the level of detection. That said, if symptoms are present, individuals should ideally continue to isolate themselves to avoid infecting others and follow local public health guidelines, if there are any. The test may be repeated a few days later to re-ascertain infection status. No lines or a faint T line indicates an invalid test. A test cannot be used more than once.

Other

Results and data from CITF-funded studies are available in a few places:

- See links to all the pages highlighting CITF-funded studies at the bottom of this page.

- See lay summaries of every CITF-funded research result available by March 2024.

- Discover CITF compiled data on Seroprevalence in Canada

- Explore the CITF Databank, which is continuing its work, the only accessible repository of individual-level epidemiological data on COVID-19 in Canada.

Core data elements are a standardized list of questions developed by CITF experts that were integrated into surveys done by CITF-funded groups studying immunity. These core data elements were developed to encourage the many CITF-funded research groups to acquire and record survey data in a standardized manner. The goal was for the CITF to be able to directly compare results from different COVID-19 studies and initiatives across Canada.

Specifically, the core data elements include questions and responses related to COVID-19 status, COVID-19 symptoms, quality of housing, risk factors, risk acquisitions, vaccines and health behavior changes related to the virus.