By Jeanie Quach

Over the past year, the world has focused on curbing the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection, mortality rates and vaccine rollout. Yet, many are unaware of the long-term effects of COVID-19 experienced by millions of individuals worldwide who have recovered from the infection. Some report COVID-19 symptoms that linger for weeks or even months after infection. This condition was termed “long COVID” or “post COVID-19 condition” and those who have it are often referred to as “long haulers”.

Why symptoms tend to persist in some people is not entirely clear. These symptoms can be diverse; they can affect individuals of all ages, with or without pre-existing health conditions. The severity of the disease (mild, moderate, or severe) does not determine whether or not an individual will suffer from long COVID. Many individuals who consider themselves previously fit and active have come to experience difficulties in performing everyday activities after having been infected with SARS-CoV-2 (1). Common symptoms include extreme fatigue, cough, shortness of breath, joint pain, and chest pain (2–5). People may also experience headaches, muscle pain, fever, heart palpitations, lack of concentration, gastrointestinal distress, loss or alteration of smell or taste, and “brain fog”, which is characterized by problems with memory, attention and multitasking (2–4). On top of coping with these symptoms, individuals report a worsening quality of life, including the inability to enjoy certain activities and inability to work.

In an early Italian study of 143 patients, participants retrospectively self-reported the presence or absence of symptoms during the acute phase of illness and whether these symptoms persisted at post-COVID follow-up (average of 60 days after symptoms onset). Of those recovered from COVID-19 (with a negative test result for SARS-CoV-2), 87.4% reported the persistence of at least one symptom, with the most common being fatigue and dyspnea, followed by joint pain and chest pain (2).

A larger cohort study in China followed 1733 individuals for an average of six months post-symptom onset to assess long-term health consequences (3). Almost 63% of study participants reported fatigue or muscle weakness, while 26% reported sleep difficulties, and another for 23% reported anxiety or depression. Interestingly, there seemed to be a greater proportion of women who experienced symptoms at follow-up. Furthermore, 22-56% of individuals across the severity scales had manifested physiological lung abnormalities six months after symptom onset. These observations seem consistent with radiological abnormalities detected in 70% of patients in a 3-month follow-up study by Zhao et al. (4), who also demonstrated lung function abnormalities in 25% of their cohort.

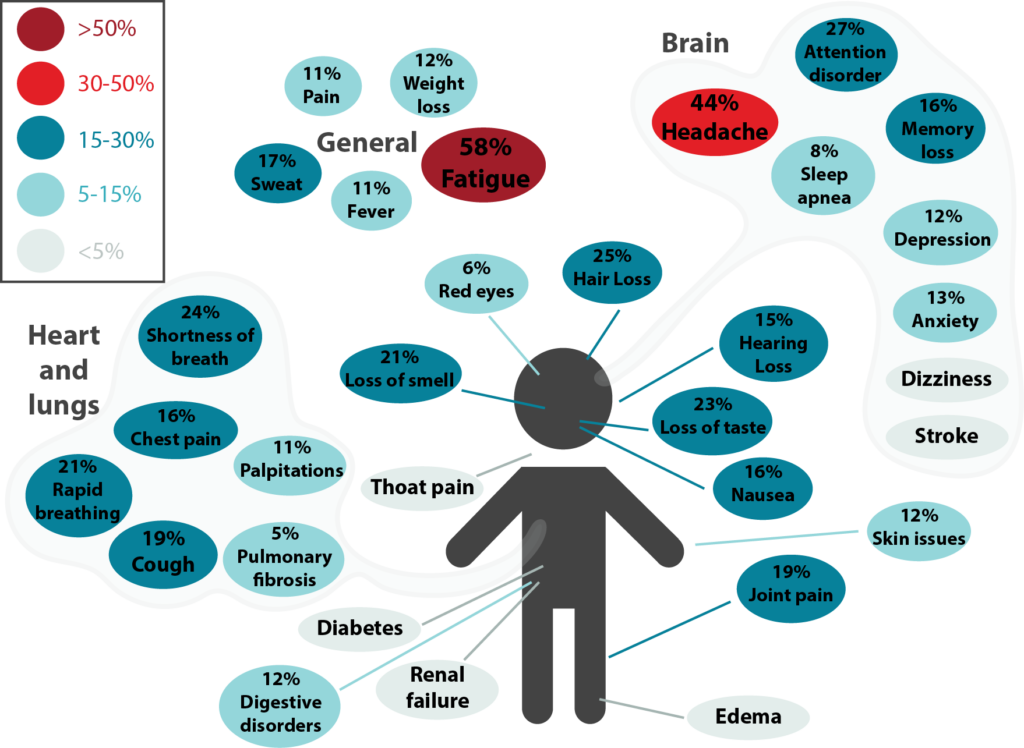

Two pre-print studies have been published, further building on these findings, with the aim of further characterizing long COVID using an online survey. One study was built on a large international cohort of 3,762 respondents from 56 countries. Davis and her team (6) found that the most frequently reported symptoms after six months were fatigue, post-exertional malaise and cognitive dysfunction, reporting similar trends to the studies from Italy and China (Figure 1). Nearly 45% of participants also reported a reduced work schedule compared to pre-COVID-19. Interestingly, in another study, Cirulli and her team did not find fatigue to be a frequent symptom, but did confirm the presence of dyspnea, chest pain, headaches, and memory loss (7). A pre-print released in January by Lopez-Leon’s group identified a total of 55 long-term effects associated with COVID-19 and estimated their prevalence through a systematic review and meta-analyses (8). The most common symptoms were fatigue, headache, attention disorder, hair loss, and dyspnea. Altogether, these reports suggest that long COVID is associated with a spectrum of symptoms and can appear to affect an increasing proportion of individuals recovering from COVID-19 worldwide.

Figure 1. Long-term effects of COVID-19. This was adapted from a meta-analysis by Lopez-Leon et al. (8) and it shows the percentage for each long-term symptom of COVID-19. Symptoms were categorized under general, brain, and heart and lungs. The most common symptoms were fatigue, headache, attention disorder, hair loss, and shortness of breath.

Now, with the vaccine rollout, this begs the question: how does vaccination affect individuals suffering from long COVID?

There was recent news that people suffering from chronic COVID-19 symptoms reported an improvement in symptoms or fewer-to-no symptoms altogether. This is extremely promising for long COVID sufferers. However, more rigorous data is required to understand exactly whether this applies to all vaccine types, age groups, or even across differing disease severities.

It is without a doubt that vaccines can decrease deaths and relieve pressure on the healthcare system. However, individuals suffering from long COVID can also pose chronic impacts on the healthcare system. These long haulers are now on the radar as many clinics have been specifically set up to treat long COVID symptoms in Western and Central Canada. There is clearly an urgent need for more information on long COVID, including the incidence in males versus females, different age and ethnic groups, and in individuals with co-morbidities. It is also important to understand how the immune responses of those who develop long COVID differ from those who do not. Researchers and healthcare professionals are still working to clinically define long COVID, the clinical course, the recovery time, and the treatment options. Hopefully there is more clarity as researchers conduct large-scale, long-term follow-up studies on these individuals.